This Is What I Do Instead of Dying

I check the news to tell me what I know the great minds easy in their thrones I rattle in my brain’s cage roll my heavy hopes uphill It takes all kinds of muscle all the animal I am to build this life and all day long to live it I check the news but no one knows me the great minds assign my worry and elation I tend their thrones it takes all kinds of toll on me I shake apart my hope unfolds my worry sediments I built this throne for you and for myself I built these wings I’m ready I rise like the dickens first published in The Yale Review (link here)

There has been, over these early months of the year, a sense of awful cruelty that has permeated nearly every action and every thought and every waking moment of each day. It is a constant cruelty. And it is a cruelty that moves so quickly that, in the time it takes to process such cruelty’s most recent exclamation — which is a time the length of which I do not know, because I find myself, still, unable to process most anything these days — the next act of cruelty has come along.

Cruelty is one word for it, and by it, I mean all of it: the ruthless deportations of immigrants, the attempts to dismantle cities that serve as sanctuaries for such immigrants, the policing of language regarding people’s bodies and sexualities and more, the wild and strange renaming of bodies of water, the threats, the takeovers, the takedowns, the crackdowns, the sneers, the jeers, the awfulness, the lies, the ruthless cruelty masquerading as honor, or patriotism, or common sense, or order, or greatness.

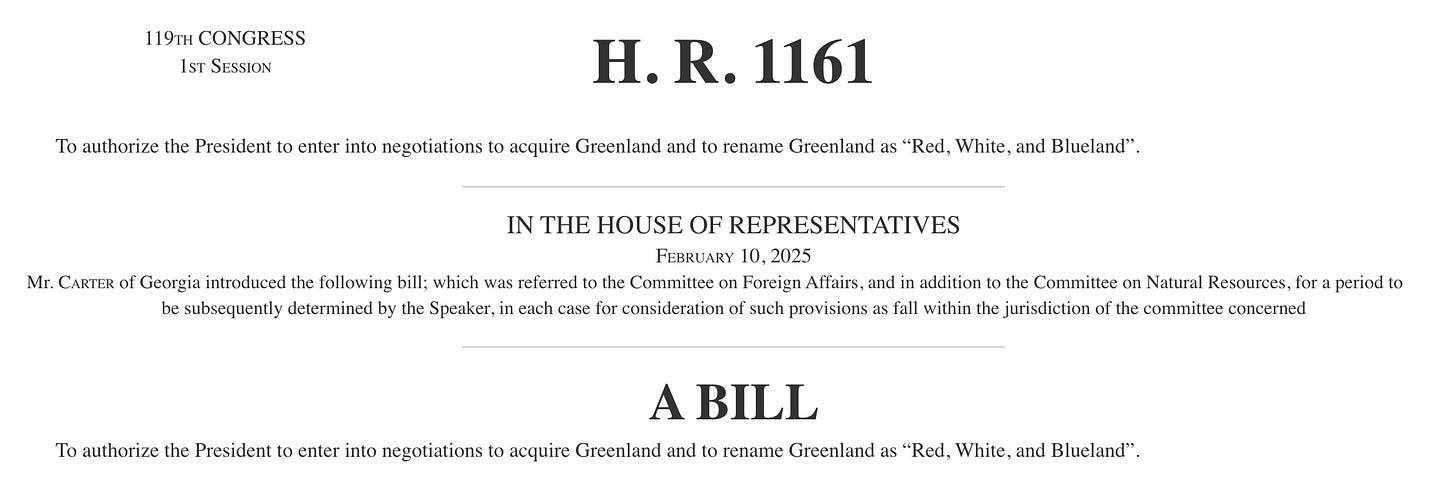

And not just cruelty, either, no. There is also idiocy. And reckless absurdity. There is the wild reality of who people are when they are given every taste of power and, at the same time, are unfettered of what they must perceive as the burden of some kind of compassionate understanding of the people we live among. Here is a screenshot of an actual bill introduced in Congress this week:

Every day feels like a test of one’s patience, and one’s hope, and one’s fear, and one’s love, and one’s comprehension, and one’s compassion, and one’s anger, and one’s rage. Every day feels a bit like failing, because I don’t quite know what to prioritize: my anger or my hope, my patience or my rage. There are limits to everything, I know. And I think we are being stretched every which way.

And so, I am thinking of this poem today by Camille Rankine, the title of which feels painfully prescient for this day, and probably each day that will follow this day for a long time. I am thinking, too, of another poem of Rankine’s, written, to use her words, “after experiencing a loss,” while, at the same time, finding “that [she] didn’t know how to mourn that loss while [she] was witnessing a genocide.” That poem begins:

I thought there was a truth we could agree on: what is loss, what is calamity.

That word, truth, repeats itself a couple more times. Here’s one moment:

In truth, I thought what if I made myself so small I never hurt again. Not me or someone else.

And another:

In truth, I had hope.

These moments of truth in Rankine’s poem are really moments of gentleness in the face of cruelty. They are moments of anti-cruelty — desires to make “myself so small,” to prioritize care. And yet, as Rankine writes about hope — such hope “softened me / for slaughter.”

It is a devastating poem because it speaks to how painful it can be to center one’s morality, one’s kindness, one’s act of constant witness, in a world where the very idea of truth — as something we can agree upon, particularly as it pertains to something like loss — has been upended. It is a devastating poem, too, because it turns so quickly. It turns, line after line, into reminders of how quickly this world has become a place where even hope can be the thing that kills us, even as it keeps us alive.

A poem can feel like the world — where each line break acts like a cliff drop, a sudden turn, a move from steadiness to insecurity, from love to rage, from peace to anxiety, from where we were to where we are.

But the truth is, too, that the cruel violence of these past few weeks began long before January. There is a long history of such violence. It is a violence that included the violence of disrupting our very idea of truth, the violence of those with power refusing to call a genocide a genocide, the violence of all of us watching, day after day, mass slaughter justified as something other than what it was. And the cruel violence began long before that. And long before that. And one of the cruelest violences of today is that the knowledge of such history — a history that enriches our present simply because it is real, even and especially if it is hard to learn about — is getting whitewashed and dismantled and censored once again. The truth is that what truth is is moving, once again, even further and further away.

I don’t know what to do in a world where even cruelty can be justified. And so I read. And I keep living. As you do, I’m sure. And so I am thinking about this poem today, which is a poem that refuses to die.

So much of what I love about Rankine’s poem is present in its opening lines:

I check the news to tell me what I know the great minds easy in their thrones

The poem begins with the mundane, the ordinary: I check the news to tell me / what I know. But then it transitions, immediately, to a kind of symbolic critique: the great minds easy // in their thrones. Here, those great minds — a kind of sardonic, tongue-in-cheek critique — can be anyone with any sort of power. The oligarchs, the president. The legacy media companies. Those with enough privilege to say none of this affects me. Rankine reminds us that there are so many thrones in this country, and, as such, so many who find themselves either unaffected or positively affected by any sort of cruelty, any sort of violence spurred on by those with power.

And I love, too, the fragmented nature of these lines: the absence of punctuation, the jagged edges, the white space. In a little blurb about the poem, Rankine writes:

Ultimately, the form felt too tidy and easy for the work the poem meant to do and its effortful movements. I found I had to disrupt the orderly pairing of couplets and introduce more irregular space…

Yeah. And so the poem, as it progresses, begins to take the shape of a mind trying to process all of this: the endless scroll of violence, a timeline of cruelty. It takes the shape of a mind trying to assemble just any sense of continuity in a world that feels forever on the verge — or in the process — of breaking.

I feel that so deeply in these lines:

It takes all kinds of muscle all the animal I am to build this life and all day long to live it

As the poem pulls itself apart into these jagged edges and floating shapes, into this realm of unpunctuated fragmentation, there is a sense of trying to keep it all together. One can imagine a body amidst all this language, a body reaching and reaching, grasping on to whatever ledge it can, pulling a word close as if it might save them, and understanding, too, that maybe nothing will.

That push-pull movement within this poem is present in other ways, too. I find myself drawn to the verbs connected to the speaker (“I”):

I check

I rattle

I am

I check

I tend

I shake

I built

I built

I rise

These verbs are verbs that situate the speaker as someone trying. They are caretaking; they are building; they are witnessing; they are coming undone as this happens. And yet, and yet, and yet. They are still rising. They are still trying.

In the midst of these verbs are two other repeated ones:

It takes

It takes

Twice, there is this taking, as if the speaker is someone — like the structure of the poem suggests — not just coming apart, but being torn apart. It is as if the speaker is gathering bits of things to make a nest, bits of twigs and dead leaves, bits of grass and dirt. But in between those moments of gathering, as the speaker pauses to catch their breath, the wind takes so much of what has been gathered away.

Today’s poem is a beautiful testament to how a poem can enact a feeling. It is remarkable in its craft. It mirrors the hollowed-out, fragmented structures we become when our care and our witness sees nothing that gives us hope, and when the energy of our witness feels like it is burning up every ounce of our fumes. When this happens, even words — as they do in this poem — can pull apart. And if language is, in essence, thought and feeling itself, and if the words, as they do, sometimes lose their meaning or their sense, or if they are, as they sometimes are, harder to find for the feelings we feel, then, I think, we start to lose our sense of who we are. That’s why I come back to reading — to find the words when I have no words. To remember, even if it brings me only some small hope, that even the darkest, strangest, scariest moment of life can be a moment shared, rather than a moment felt alone.

As I did last week, before I close, I’d like to mention a little something. I am in the middle of teaching a virtual class for the Adirondack Center for Writers. It’s called You Do Not Have to Be Good, and it’s on reading and writing with generosity in mind, on moving away from a restrictive and prescriptive method of such things that can label things in ways that feel reductive rather than expansive.

I’ve asked my students to, in the week between classes, engage in reading and writing prompts that feel, at least to me, like some small way to try to read a poem and then look at the world and then try to approach any of it — however hard — with generosity. I’d like to offer the prompts here, each week, as well — in case you, reading this, are interested. I don’t want to gate-keep every aspect of that class. And I’d like to answer them myself. Here’s this week’s prompt:

Read, as a guide, Steve Scafidi's poem "Among the Millions of Things That History Will Forget." It's beautiful, isn't it? He is one of the poets who changed my life. Really. I mean that.

Then, in a little mini essay or a poem or whatever you want, make your own list of things that history will forget but that you, alive right now, will not. It can take the shape of a list. A grocery list, even. It can take the shape of a poem. It can take the shape of a story. Whatever you want.

And here’s that poem:

And so, for me?

There’s the child I saw a block up from the corner of Wales Ave and 149th Street, pointing their phone up to take a photo of the snow-covered branches of a tree.

There’s how I felt in that moment, a little stunned, carrying two dozen donuts for one of my classes that was about to perform a bunch of memorized poems, an old-school assignment that calls for radical attention, my mornings filled with students walking around the hallway, their friends holding laptops, checking to see if they know every line.

There’s how that sense of being stunned gave way to gentleness, and how there’s a ghost of me that paused to watch the photo being taken, and then stayed a little longer to watch the tree.

There’s the neighborhood deli’s flower man, trimming roses under the light of a single bulb an hour after closing, a six-pack of Corona on the table beside him.

There’s the memory of buying hydrangeas from that same man on my wedding day.

There’s what I’m holding on to.

And what I will forget.

There’s how I know, right now, that I will forget.

And there’s how I’m holding on to that.

Some notes:

You can find a list of the work that Writers Against the War on Gaza is doing to build solidarity among writers in support of Palestinian and against their consistent oppression here.

Workshops 4 Gaza is an organization of writers putting together donation-based writing workshops and readings in support of Palestine and in awareness of a more just, informed, thoughtful, considerate world. You can follow them here and get more information about them here.

If you’ve read any of the recent newsletters, you’ve perhaps noticed that I am offering a subscription option. This is functioning as a kind of “tip jar.” If you would like to offer your monetary support as a form of generosity, please consider becoming a paid subscriber below. There is no difference in what you receive as a free or paid subscriber; to choose the latter is simply an option to exercise your generosity if you feel willing. I am grateful for you either way. Thanks for your readership.

"Every day feels like a test of one’s patience, and one’s hope, and one’s fear, and one’s love, and one’s comprehension, and one’s compassion, and one’s anger, and one’s rage. Every day feels a bit like failing, because I don’t quite know what to prioritize: my anger or my hope, my patience or my rage. There are limits to everything, I know. And I think we are being stretched every which way." - a devastating poem, devastatingly beautiful analysis of it, and devastatingly accurate reflection on these times we stay alive in.

Thank you, Deving for finding this poem and your analysis of it. You even managed to bring back last week's theme tenderness through your words and your reminder of poetry's role, that of witness.