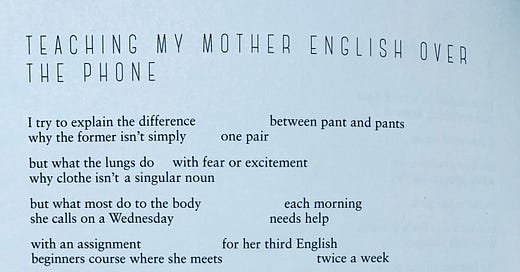

Eloisa Amezcua's "Teaching My Mother English Over the Phone"

Thoughts on language and permission.

from From the Inside Quietly (Shelterbelt, 2018)

I spend a lot of time in these little essays talking about what a poem can do, but, I mean, come on, look at what a poem can do. I have this poem filed away as one of my favorite poems to teach. It’s up there with Robert Hayden’s “Those Winter Sundays” and Yusef Komunyakaa’s “Facing It” and Kim Addonizio’s “What Do Women Want” — all poems, among many others, that change the way we witness the world we exist within, that change our perception of a feeling, an object, a desire, or language itself. I think poems, even in their most sorrow-filled testimony, are elements of play. Play is so often associated with a joyful output. I think that’s wrong. People break their bones when they play. They bleed. They fight, sometimes. They end up crying. But the play itself, this marvelous making-of-the-world into something that could be joyful, is an act of joy. Even in sorrow, I think. Maybe I’m wrong.

I love the play of this poem. I loved it the moment I read it. I love the lines that read:

I try to make the language clear to my mother

as she one day —before my English took hold—

explained to me that I did not in fact make friendswith a girl named Sorry

One beauty of this poem is the way it exposes the myriad fault-lines that exist within language, which is another way of exposing the difficulty of language itself, which is another way of exposing why it is so hard, sometimes, to say anything to anyone. But more so than that, the poem finds some kind of joy in this inability. It plays within that inability, and in doing so, it exists within this in-between, stuck between the permissiveness of play and the sadness of inability, of not being able to say what you are able to think, of not being able to say, simply, what you want to say — something about love, or apology, or forgiveness, or anything as true as what we feel.

I think I’ve quoted these lines before, but I always return to Jamaal May’s poem, “Macrophobia,” where he writes:

I kept fiddling with my phone through dinner

because I was fascinated

that every time I tried to type love,

I miss the o and hit i instead.

I live you is a mistake I make so often,

I wonder if it’s not

what I’ve been really meaning to say.

At the heart of Amezcua’s poem, perhaps, is a question related to those final lines from May: what is it that we are really meaning to say? And, perhaps, at the heart of it, too, is another question: what are we capable of saying that we don’t give ourselves permission to say?

As a high school teacher, I think of that second question a great deal. I don’t want to use this poem as a platform to talk about the pains and possibilities of grammar, but I’ll say, simply, that I spend a great deal of time unlearning how I learned grammar and rethinking how I might teach grammar. That lonely line in Amezcua’s poem — that’s not how this works I remind her — is probably a line a number of teachers have uttered to students, perhaps in varying degrees of damaging ways. It’s a line of frustration, exasperation. It’s also, I would argue more importantly, a line of utter loneliness on the part of the recipient of such a sentiment. To be unable to say what you are trying to say, to be told that what you are trying to say isn’t how it is supposed to be said — what could be more lonely than that?

I think so often of the time I’ve spent teaching idioms as part of test prep classes to students who did not grow up with English as their first language. I think of the difficulty of that, the frustration, how it was like teaching things that don’t make sense to people who would say hey, this doesn’t make sense. And how I’d have to be like yeah, you’re right, but then keep teaching those nonsense things because, for some reason, those nonsense things mattered. I think of how standardized tests such as the SAT have a deeply racist origin story. And I think of the way — in this case, English — grammar privileges those who know enough about its structure to break the rules of that structure, and yet does not honor those who bring their own knowledge, insight, and structural understanding to language without being privy to the specific workings of English grammar.

And so, I perpetually wonder, how might we give ourselves permission to say what we are trying to say in the ways in which we are trying to say it? And those who are tasked with determining how that permission might be granted or received — how might they rethink what it means for something to work, for something to be right? How might they learn, or unlearn, or relearn? Why is play in our language a kind of privilege? Why can’t playfulness be how we learn? Don’t we learn so many things through play? What is failure if not one of the only bad words?

One of the many beautiful things about poetry is the way it offers new understandings of what language is capable of, and, maybe more importantly, what people are capable of producing and saying and feeling with the structures of language that are so often used as tools of oppression. Today’s poem is no different. It showcases not only the intricacies of language, how “a word can be both / a thing and an action,” but also the intricacies of love:

I love you love he loves she loved

we loved you have loved I am loving

I think of these lines from Solmaz Sharif’s poem, “The End of Exile”:

From bed, I hear a man in the alley

selling something, no longer by mule and holler

but by bullhorn and jalopy.

How to say what he is selling —

it is no thing

this language thought worth naming.

No thing I have used before.

Each language, I imagine, has words and things it has deemed not worth naming. Perhaps it hasn’t even thought of them. And perhaps, most likely, that is the result of power, and the way power limits perception through oppression. There are so many things — and by things, I mean feelings, desires, what is whispered and yelled and everything in between — that have yet to be said, that have been felt but not uttered, that have been wanted but not received. Poetry offers the permission to say such things, and to say them in certain ways. To say them without any affinity toward the rules of grammar. To say them with mastery of grammar, and, with such mastery, a kind of play (read any Carl Phillips poem and you will know what I mean). To say them by slicing the ly off an adverb. To say them by verb-ing a noun, as Bradley Trumpfheller does quite often, and quite beautifully, such as here, with the word centerpiece:

My aunts spell

around the vanity mirror

& centerpiece me

And so, to return to today’s poem, I want to name that there is joy in it, even if it ends in apology, even if it ends in sorrow, even if it ends in a kind of failure. The joy is in what is tried. The joy is in the trying-to-say. The joy is in the nonsense, too — what, no matter how many times you can possibly explain it, will never make sense at all. There is clarity in understanding, yes. I know this. But there is a different kind of clarity in accepting what cannot be understood.

There is also joy, too, in the fact that I learn from this poem. When I first read it, and found myself looking at that final line “I haven’t taught her anything,” I smiled just the smallest bit. Because I learned something. And I know that, in the event of this poem, that might not be the point. And yet, in reading this, I gasped that the plural of dust is not dusts. And I gasped at the dual capabilities of words such as war and mistake. I was awakened to numerous potentials. I was surprised, as I am, so often, by the students I teach — so often that I know I should not be surprised at all. I found myself intellectually humbled. I found myself learning. And there is joy in that, too. I sometimes forget. Maybe you do, too? How fun it is to learn. How fun it is to learn and be loved at the same time. To feel safe in both acts. What a joy that is. I find it in this poem. It’s a reason why I read.

Like you say, poetry gives us the freedom to play through artistic creativity, and ponder what it means for something to work and for something to be right. But as a fellow educator, I'm always a little haunted by where the line is between what's working/right and what isn't working and what's wrong. For so long, like you intimate by bringing up the racist origins of the SAT, there has been a narrow, biased, and incomplete hegemony on right and wrong. But moving equally subjectively in the other direction only mires us in solipsism. At least I think.

One day, I was tutoring a student on how to annotate and write about Sylvia Plath's poem, "Spinster." And the student thought the poem was more about how courting in Plath's time was more like a game, similar to the card game Plath invokes in her characterization of the heroine's 'queenly wits.' Which . . . Felt wrong. As true as that was, to me "Spinster" is less about the game of love and more about the heroine's difficulty reconciling her suitor's imperfections and her retreat into solitude at the expense of any love at all. So I told him that. I told him his interpretation was wrong. And I hate that because again, what works? What is right?

In preparing to be English teachers (or at least in my preparation) they tell us that if a student can back up their interpretations with relevant quotes--if they prove their point--they deserve full credit, no matter how wrong that interpretation feels. And in Lit Theory, we're asked to be skeptical about a writer's biography and own intent in deciding the right and wrong ways to experience their work. I guess all this is to say that like with poetry, in academia we play with meaning. I just wish it gave us clearer answers.