Untitled

Someone turns a light on in a house down the road it must be a man going over all the words he ever spoke all the fields he ever left on his way to open a door. from What About This: Collected Poems of Frank Stanford (Copper Canyon, 2015)

I don’t own many books of collected poems, but I cherish the ones I do. Galway Kinnell’s. Louise Glück’s. Zbigniew Herbert’s. Mark Strand’s. Mary Oliver’s. And then there’s Frank Stanford’s.

There’s something about a book of collected poems that feels like one of the cherish-able totems of any time. It is as if, holding such a book, you are holding one of the closest things that could possibly resemble a life. Collected, the book’s title reads. As if we are these walking things, leaving behind crumbs of who we are along the paths we walk along. As if we are meant to be held by someone other than us. Gathered up, someone might say. Collected. Placed in a jar. Between the covers of a book.

I don’t know if I could collect my own life. I’d need your help. I’d need you to see me for who I am, and for what I leave behind. I’d need you to help gather me up. The way I scatter papers on my desk and leave them there. The way I write marginalia on all the margins I encounter. The way I am skin-dust and nail scrap, dead hair left in the bathtub’s drain. The way I am the crush of already crushed cinder on the trail between the trees. The way, walking with you, I am a lost hat in the wind. The way breath becomes word and word becomes air and air becomes breath and breath becomes word again. The way I am and the way you are. The way I listen to you across the table in a dark room. The way you listen to me. Collected things we are. Always holding one another in our arms.

I particularly love Frank Stanford’s Collected Poems because it truly feels collected. Stanford’s work is the stuff of earth and dreams and dirt and roads and rooms and all the dust in between. One of my favorite poems of his, simply titled “Poem,” reads:

When the rain hits the snake in the head, he closes his eyes and wishes he were asleep in a tire on the side of the road, so young boys could roll him over, forever.

Are you kidding me? What an image. Have you ever thought of how rain feels to a snake? Or joy?

And maybe that’s one of the many reasons why I love Stanford’s Collected Poems so much — it is a book filled with poems that are untitled, poems that read as if they were written under bare-bulb light on the backside of a napkin, poems that read as if howled in a field of one’s own making, poems that feel scratched into the woodwork of a wall, poems that feel penciled into mud with a stick, poems that feel whispered once and then never spoken again, poems that lived once as dreams and then again as dreams on paper.

Yes, indeed — one of Stanford’s poems, “quest of chants,” reads, in entirety:

I dream and it is another life

There’s something about today’s poem — and all of Stanford’s work — that reminds me that the work of poetry is partly the work of figuring out how to access a weird little doorway to one’s soul, and then to figure out — harder, still — how to allow someone else to access that same doorway, too. It is the work of wondering why you are spellbound by the sight of a light on in a field across the way, and then figuring out the language of that wonder, so that someone else can wonder alongside you. One beauty of poetry — of many — is this invitation to wonder together, a kind of gathering-up of everyone alongside a railing where, on the other side, is everything you don’t know. It shines with light. It shimmers. It goes dark and then shines again. You say ooo. You say ahh. You say holy shit. You say I never knew. You say I still don’t. And you say it all together.

I think of these lines from today’s poem:

a man going over all the words he ever spoke all the fields he ever left on his way to open a door.

This, I think, is one way of describing what it feels like to figure out this doorway to the soul, this space where we keep what we obsess over, and where it becomes whatever it becomes — a field on the other side of a door. When I read Stanford’s poetry, I feel it. I think that it is because his poetry has this sense of the soul, this intangible, inaccessible thing that is alive but is forever lost until we find it. And then it is lost again. And then found again. And you come to realize, maybe, that it is the searching that matters. How do you write a poem? There are a million ways multiplied by infinity. But one way, I know, is to treat life as an act of listening. So that even the snake asleep in a tire and the man turning a light on in a house down the road are telling you something. And the wind-rustle, too. And the patter of rain on the window. And the smell of bread. And a child, kicking a basketball as if it were a soccer ball.

When you do this, I think, you get lost a thousand times a day — lost in thought and lost in your mind, and lost in the search you were on. You get lost toward something, too. And that’s cool. There’s probably a poem there. Find it.

Stanford’s Collected Poems is filled with these moments of listening to the world, of watching lights turn on in distance places. Here’s a snippet, from “When We Are Young the Moon Is like a Pond We All Drown In”:

I feel like a lamp someone is holding up looking for a way through a dark field I will go out

It’s also filled with moments of feeling lights turn on — or turn off — inside one’s soul. Like here, in “Whistling with His Teeth in a Jar”:

I heard sorrow again Up in my lap

When I was younger, before I wrote poems really, or before I really thought of myself as someone who wrote poems, I was obsessed with looking out the backseat window of my dad’s car as he drove my brother and I to Rochester — the city where my dad grew up and where his mother lived until the day she died. My dad always made the drive at night, and toward the end of the drive, as we moved what-felt-like-silently through towns on the northern side of the New York state line — Corning, Bath, Dansville — I stared out the window at gas station glow and the distant yellow of windows lit in houses I would never set foot in. I was 10 years old. I was 11 years old. I was 13. I was 15. I looked into those windows, and I imagined. I wondered about the people in those rooms, and if they sat at tables without talking, or if they ever stared out the window into the darkness and felt at least a little bit sad.

It’s funny. We drove the same route every year, and, thinking about it now, I lost myself in it every time.

One of the first poems I ever published — which no longer exists online — had these lines below at its heart. I had to dig around to find them:

Before my mother left she gave me books of great beauty. I read them & did not know then what Frost meant when he wrote of fences. All those homes littered on that long drive through the county lines. & all those people I will never know the names of. In that cramped car with my father & brother, I pressed my cheek against the cold glass of a window & before sleep dreamed of mothers. After Dansville, some homes glowed yellow under outer dark, as if each knew some child was watching, & burning, too. Refrigerators tacked with photos of other families.

That was nearly a decade ago, if not over a decade ago. Unbelievable. It’s funny, what doesn’t leave us. I think I have been thinking of what I don’t know for the longest time. I feel like a man / going over all the words / he ever spoke…on his way to open a door. I wonder what that door will be, and where I’ll find it. And I wonder what’s on the other side.

Stanford has a wildly short poem in his Collected. It’s titled “To Find Directions.” It reads:

Go to the graveyard.

I think that maybe part of life — which means, too, part of writing, which means, too, part of poetry — is not necessarily about finding direction. If we need direction, well, we all know where we are ultimately headed. What, then, are we looking to find? If not direction, then what? I don’t know. Maybe that, too, is something worth finding. More of that. More of what we don’t know. I think of a book of collected poems. I think of shells on the beach. Rocks burnished by wind and water, almost polished by the world. I think of what people pick up for us, all we’ve dropped. The way they offer it back to us. The way we say I didn’t know I lost that, which is another way of saying I didn’t know I was lost, which is another way of saying I know I’m alive. We remind each other, all the time, of what we’ve dropped, of what we’ve lost. We pick each other up and give each other back to us.

Before I close, I’d like to mention that I began teaching my second section of a class for the Adirondack Center for Writers this past week. If you’ve read this far before, and recall, it’s called You Do Not Have to Be Good, and it’s on reading and writing with generosity in mind, on moving away from a restrictive and prescriptive method of such things that can label things in ways that feel reductive rather than expansive.

I’ve asked my students to, in the week between classes, engage in reading and writing prompts that feel, at least to me, like some small way to try to read a poem and then look at the world and then try to approach any of it — however hard — with generosity. I did this with the first session, but I’d like to offer the prompts here again— in case you, reading this, are interested. I’ll be answering them again myself, which I’m excited to do, given how the prompts are the same, but my life — as yours is — is a little different. And so, here’s the first week’s prompt:

As a guide, read Jim Moore's poem, “I'd Like to Say This as Clearly as Possible.”

Then, write a short paragraph/little mini essay that uses Moore's poem as a guide or model to approach looking at the world. By that, I mean: consider the phrase "I live in a world in which" and then go from there. Maybe this looks like a piece of writing that reflects on something specific and beautiful about the world. Maybe it looks like you feeling moved — to joy or sorrow — about something you witnessed at the dog park. But the idea is still the same — what is it you notice about the world, this world, this world in which things happen?

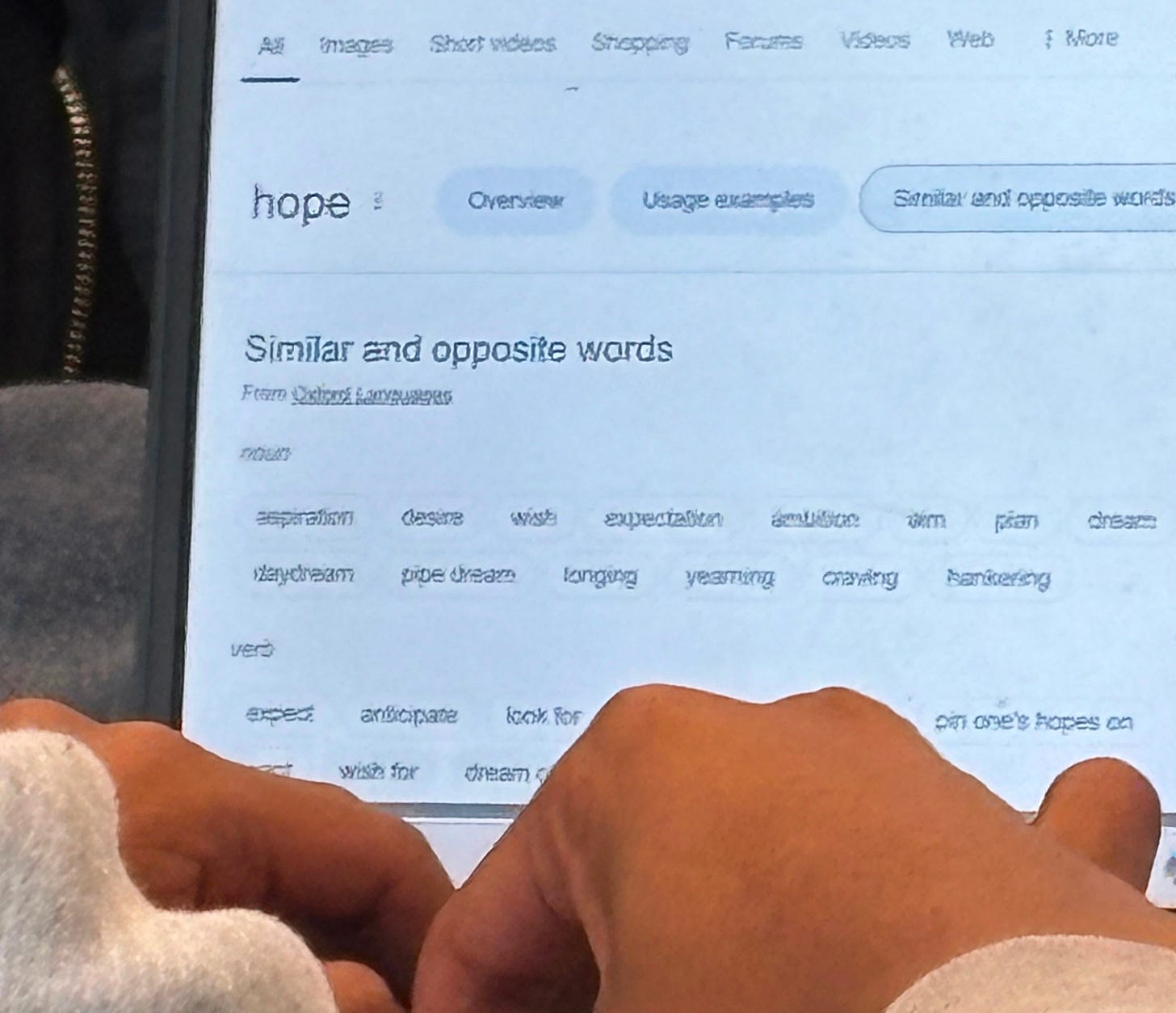

I live in a world where I sneakily took this photo while one of my students was working on an assignment.

I live in a world where, while sitting near this student, I watched him look up different words for hope. And I thought, then, of the phrase thirteen ways of looking at a blackbird. And I thought, too, of hope is a thing with feathers. I live in a world in which I thought those thoughts, and a world, too, that is a world of those words, and was once a world where someone sat down and made those words. But really, and maybe most importantly, I live in a world in which someone was sitting down — not too long before the time in which I am writing this — and looking up different words for hope. And I live in a world where hope is both a noun and a verb, both something we desire and also our act of longing and wishing and believing in such a desire. I hope, sometimes, for my hope. I do this every day. I live in that world, too. Which is this world. Sometimes I hope for what is beyond my hope, and sometimes — actually, often — I hope for what is less than my hope. I make concessions for my hope. Just so that I don’t have to hope anymore. Because hope feels, many days, like work. That’s a world I live in, too. A world where hope feels like work. Sometimes wasted work. Which is wasted time. Which is the worst kind of work, and the worst kind of time. I live in that world, too — a world where time can be wasted, or can feel as if it is wasted. I live in the sadness I often feel when I feel I have wasted time. But then I also live in a world in which I am reminded. As I was the other day, seeing this. Reminded, yes, of some small thing. Nothing big. Just a synonym for hope. A million ways to think of what we long for. Dream. Wish. Yearn. Crave. Believe. Part of the world we live in is this belief that it will become something better. This world holds that world at its heart. I live in this world, holding that world at my heart.

Some notes:

Here is a website — put together by volunteers — that tracks the jobs lost and lives affected by the de-funding of USAID. It’s worth reading in order to fully understand the severity of what is happening, who it is affecting, and how to help.

You can find a list of the work that Writers Against the War on Gaza is doing to build solidarity among writers in support of Palestinian and against their consistent oppression here.

Workshops 4 Gaza is an organization of writers putting together donation-based writing workshops and readings in support of Palestine and in awareness of a more just, informed, thoughtful, considerate world. You can follow them here and get more information about them here.

If you’ve read any of the recent newsletters, you’ve perhaps noticed that I am offering a subscription option. This is functioning as a kind of “tip jar.” If you would like to offer your monetary support as a form of generosity, please consider becoming a paid subscriber below. There is no difference in what you receive as a free or paid subscriber; to choose the latter is simply an option to exercise your generosity if you feel willing. I am grateful for you either way. Thanks for your readership.

I love this poem and your reflections on it. I am unfamiliar with Frank Stanford. Will definitely be seeking him out. Such beautiful poems. Today’s reminds me of a Ted Kooser poem from Winter morning walks:

January 10

Eight degrees at 6 a.m.

Cloudy and cold, the moon like a lamp

Behind a curtained window,

And who could be sitting alone in that room

With its dusty, ancient furniture

If not a god?

"One beauty of poetry — of many — is this invitation to wonder together, a kind of gathering-up of everyone alongside a railing where, on the other side, is everything you don’t know."

Art opens a chasm at one's feet, inviting us into unknown worlds. Thank you for today's writing.