Gabrielle Bates's "I Asked // I Got"

Thoughts on re-imagining.

I Asked // I Got

after Brigit Pegeen Kelly

for honey: gravel in a thousand shaken cans for genius: the dream in which my grandmother cooks two eggs for an understanding of the past: a boat crossing the window; the room sliding backward for attention: anything ripped in the middle looks for a mother to be honest: Sharon Olds / Lucille Clifton / Brigit (is it OK if I call you...) for another life, adjacent, and wilder: trapped clouds in the plant conservatory for a doorway: a beautiful woman, backlit, eating cornbread off a knife from Judas Goat (Tin House, 2023)

In her notes at the back of the beautiful book — Judas Goat — that today’s poem is from, Gabrielle Bates writes that today’s poem is “partially inspired” by Brigit Pegeen Kelly’s “final published poem,” titled “Closing Time; Iskandariya.”

That poem, a long, winding, almost-one-single-sentence filled with tangents and asides and qualifications and descriptions, begins:

It was not a scorpion I asked for, I asked for a fish, but maybe God misheard my request…

It’s a poem that, perhaps strangely, reminds me of that oft-quoted Mary Oliver question:

Tell me, what is it you plan to do with your one wild and precious life?

I don’t read these lines — as some people do — as a kind of motivating push to make something of your life, but rather as a reminder of how life — strange and uncertain as it is — so often makes at our plans a kind of wry, playful smile. And I think of that smile, that playfulness, as I read Brigit Pegeen Kelly’s poem, which, yes, begins with a plan gone awry. Once you read this poem, it enamors you — I hope — with its attention and sensitivity and more. It is filled with little moments of joy and strangeness, like this one conclusion, brought upon by the speaker’s surprise of her newfound attachment:

In truth, it is shy, the scorpion, a creature with eight eyes and almost no sight, who shuns the daylight, and is driven mad by fire, who favors the lonely spot, and feeds on nothing much, and only throws out its poison barb when backed against a wall — a thing like me, but not the thing I asked for, a thing, by accident or design, I am now attached to.

Or, here’s another moment of profundity and a little bit of humor, when Kelly writes:

because God, too, forgets, everything forgets

Which, as an aside, echoes another little moment from a different book — Lewis Hyde’s A Primer for Forgetting, where Hyde writes:

Let us then reclaim forgetting as a component of truth, there being “no Aletheia without a measure of Lethe.” When a diviner or poet penetrates the invisible world, Memory and Oblivion both are present. And what is the name of this double thing found at the seam of silence and speech, praise and blame, light and darkness? Call it imagination, call it poetry.

And so I love so much about today’s poem and the poem that it draws its inspiration from. And I love, too, that conversation. The one between Bates and Kelly, how Bates saw in Kelly’s work a conceit — this notion of certainty and uncertainty and surprise, of wanting and not getting, of making do, of figuring out, of living a life made out of the strange and sometimes lovely space provided by dissonance and desire.

And craft-wise, what I really love is how Bates turns this conceit of Kelly’s poem into a structure all her own. And it’s a beautiful — truly, I mean it — structure for a poem, this idea of crafting a dialogue with oneself out of what you have asked for — honey, genius, and more — and what you have received instead. It is playful and yet serious and exactly what Lewis Hyde describes as poetry in his passage above — a “double thing found at the seam of silence and speech, praise and blame, light and darkness.”

Yes, today’s poem gives language to the “double thing” that is so much of life. Such a poem requires humility — because what is more humbling than receiving something different than what one has asked for? And it requires, too, attention — because what is more attentive than looking, and looking, and looking again at the world and seeing not the absence of what you wanted, but rather the thing or idea that has come to fill the space of your desire? And it requires, finally, care — because what is more care-filled than looking closely at such a thing, at whatever has come to fill the space of your desire, even if it is not what you desired?

It’s like how, in Brigit Pegeen Kelly’s poem, something a lot like love — I think, maybe, that it is love — arises out of the attention offered to the scorpion. In a poem, you can give structure and space to an idea, and witness how, in the safety of that space, language — what passes, at first, for mere description, cataloguing, reporting — can become something a lot like love. That’s beautiful, I think. I find it beautiful to read language stitching this life of doubleness and strangeness and desire and doubt into feeling. Because it is in feeling, I think, that we find something together, despite all we know that is different.

Bates enacts that stitching-together in her poem today. It becomes, her poem, a surprising and striking enactment of what poetry can do — how it uses an almost-invisible thread to allow the reader to consider what they, perhaps, have yet to consider. It casts light on ideas and then allows them to become further interpretations of themselves through the act of being read.

“Honey” becomes:

gravel in a thousand shaken cans

And “genius” becomes:

the dream in which my grandmother cooks two eggs

And “an understanding of the past” becomes:

a boat crossing the window; the room sliding backward

And so on.

Such moments of becoming reveal how wide and generous the very idea of a life can be, even when it feels difficult or painful or, simply, different than expected. And such moments also reveal how generously one has to look at a life in order to reveal the generosity at the heart of life. That’s difficult work. It’s a poet’s work. It’s the work Bates performs in this poem. It’s almost miracle-work isn’t it? How it turns what could be absence — the thought of not getting what one asked for — into fullness and dreams and more, all without making or producing anything. Just by looking.

It’s work, too, that Bates does throughout her book, such as in her poem, “Garden,” which ends with a realization — an admittance of mistake, a re-defining of a word, and, as such, a life:

I've mistaken the word so long, cold for clean—

Or, in “Salmon,” a poem about a father, how it offers a way of understanding that a life can be many things at once:

I know his regrets. I could list them. But instead at his funeral I will talk if I can about nights like this, how good it felt just to be next to him, to be the closest thing he had.

I’m struck, especially, by how such work allows for re-imaginations of what life can be. And how lovely, ordinary, and humbling such re-imaginations are. Like how the word genius in today’s poem is allowed to be reframed as the image of a grandmother cooking. This is beautiful, and true.

My own grandmother died nearly a decade ago. I was young, one of the youngest of her grandchildren, and I think often of how I could have asked and witnessed and wondered in the time I had with her. How I could have simply stood beside her to watch how she powdered sugar over a walnut cookie, or how she battered the chicken that she’d then, after it cooked, coat in a sauce of white wine and lemon and butter. Chicken French, she called it. But the food just appeared when I was young. I never thought to watch. Or ask about how it was prepared. I never knew the stories. I never wanted them to be told. And yet now, older, my grandmother gone, I miss the food, yes. But I miss, too, what I never gave myself a chance to even witness. I miss the making. And I miss what could have filled the absence I now have in my mind. I see it as genius now, yes — my grandmother’s life, which is perhaps true of every grandmother’s life. The way it was beautiful and ordinary and there, right there. And how I only had to look.

I’m struck, also, by a moment like this:

for another life, adjacent, and wilder: trapped clouds in the plant conservatory

What striking craft, to use the word trapped to get at something wilder. What a juxtaposition of ideas. Here, in the asking for something wilder, the speaker is given something perhaps seen as smaller, even tamed. And yet, and yet, and yet. It is the looking that matters. In this moment is illustrated the beauty of looking — how, feeling yourself perhaps trapped in a life that you wish was another, and how, wishing for something different, you might find yourself walking through a garden, or, I don’t know, sitting on your fire escape, or looking out the open window of a car’s passenger side, and, I don’t know, seeing something move between the stars or noticing how light makes of one color something different or feeling the breeze make of your face a mix of flower-scent and ocean salt, and then — wow — your life, having caught that moment, briefly, in the little jar it sat in as you moved through it — well, it’s different, isn’t it? It’s not another life. It’s the same one. But it’s yours again. You’ve gone back to feeling it.

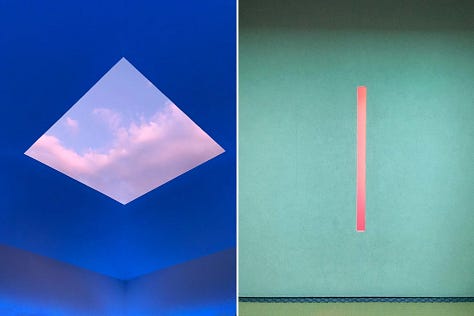

I think of James Turrell’s Skyspaces — these fixtures of art where Turrell, in some ways, structures the way we view light. Some might say he traps it, although that’s impossible, given that we are governed by light and not the other way around. But he does offer a shape through which we might look at light. And I think that’s part of the point — that, by giving us a structure through which to look at light, we finally look at it. And are moved by it. And even changed. Sometimes it’s all too much. Sometimes the world is too big. And sometimes we need someone or something to say it’s okay — just look over here. And I think that, too, is what Bates illustrates in today’s poem. When we ask for a different life, we perhaps calibrate our attention towards searching, witnessing, and looking for that different life. And then, maybe even strangely, but definitely beautifully, we realize we can find that different life in our same life. We notice the clouds, perhaps, for the first time in a long time, because we have given ourselves the space to look, finally, for the first time in a long time.

Just the other day, I went with my wife to Turrell’s installation at MoMA PS1. You walk through a closed door, from an air conditioned hallway into an absolutely silent room with a perfect rectangle cut out of its roof. The silence overtakes you, until you realize it is not silence. There, in the distance, the crush of a bus getting its engine going. Birds, too. And the aimless, wandering chatter of friends floating up from the street that must surely exist out there, wherever there is. But even this, all of this sound, feels different. It is as if you finally, for the first time, allowed yourself to breathe out. And up above: the sky. Stunningly, remarkably ordinary. Just blue. Just passing by. Yes, it is your same life. Yes, it must be. And oh, I found myself thinking, how much it contains.

I’m thinking, too, as I think of all of this, of a short poem by Linda Pastan, titled “The New Dog”:

Into the gravity of my life, the serious ceremonies of polish and paper and pen, has come this manic animal whose innocent disruptions make nonsense of my old simplicities— as if I needed him to prove again that after all the careful planning, anything can happen.

That final stanza is where life and poetry intersect. I think of Carl Phillips’s My Trade Is Mystery, and how, in that book, he writes:

Poems, for me, are deeply private, as is the making of them. I’ve no idea how I do this thing, ultimately. Nor do I want to know. To be given a map or compass would prevent my getting lost—what, for me, the making of poems requires from the start.

Later, he echoes that same idea:

For me, at least, art is the result of my having allowed myself to stray from any marked path and to become lost.

Finally, he ends that chapter with a question:

Is it maybe better not just to respect but to committedly embrace knowing’s limits?

And isn’t that what Pastan’s poem does? What the dog reminds the speaker of, as the dog runs through the poem? To embrace it — small, howling, tumbling, lovable thing — and all it represents about embracing, too, the very limits of knowing and planning and making certain? And isn’t that what Bates’s poem does today? What it makes and remakes of what it once felt certain of, and, by the fact of such certainty, asked for? And what it imagines and reimagines of a life by making oneself lost again so that one might look again? And isn’t that what Kelly’s poem does, too? How, lost at the fact of God’s forgetting, the speaker doesn’t step away from such lostness, but rather steps right into it, and finds, in such lostness, maybe something like love?

And so yes, because of Bates’s poem today, I am thinking of what poetry makes possible. Not out of nothing, no. But out of life — by which I mean, out of mystery, and out of not knowing, and out of once knowing and now realizing you don’t, and out of desire, and out of the sorrow of failed desire, and out of the empty space provided by that failed desire, which is not really empty, but filled with something, if you care enough to look, and out of that, the looking, and out of grace, and out of humility, and out of doubleness, and out of uncertainty, and out of care, and out of love. And into all these things, too. Not just out of. And into love, yes, especially.

Some notes:

As I will continue to mention, Writers Against the War on Gaza has been a powerful resource that has, in these days, reminded me of all the various potentials for solidarity in this moment. You can follow them on Instagram here. Here, too, is a link to the New York War Crimes page — their ongoing publication.

If you’ve read any of the recent newsletters, you’ve perhaps noticed that I am offering a subscription option. This is functioning as a kind of “tip jar.” If you would like to offer your monetary support as a form of generosity, please consider becoming a paid subscriber below. There is no difference in what you receive as a free or paid subscriber; to choose the latter is simply an option to exercise your generosity if you feel willing. I am grateful for you either way. Thanks for your readership.

Thanks (again) for these poems—all of which were new to me—and for your thoughtful and perceptive articulation of the questions and connections that arise in your mind as you read them. I sometimes find myself wondering whether the time I spend on reading and writing poetry is time that might be better spent doing something—anything?—else. You make the case FOR very eloquently, in this post and in so many of your others. I particularly loved the way you pose this question: "...what is more attentive than looking, and looking, and looking again at the world and seeing not the absence of what you wanted, but rather the thing or idea that has come to fill the space of your desire."

So many of my favorite people and ideas in one place: this poem, Gabrielle, Turrell, the generosity of paying attention, the reimagining of what life can be. A gorgeous reflection on an equally gorgeous poem.