(A note: this poem is sad.)

from Something Sinister (Carnegie Mellon University Press, 2016)

Okay. Yes. This poem is utterly devastating. We can all just sit with that for a second. It is devastating in subject matter, devastating in the moment that prompts the moment of the poem, devastating in the moment that occupies the poem, and devastating in the moment that will inevitably end the poem.

I am only a little sorry for ruining your morning with it.

I do love Hayan Charara’s work. This book in particular is a favorite. His work does such a powerful job of exploring the many vagaries — some sinister, some cruel, some unexpectedly kind — of living life, particularly in America. This poem is less about that and more about something more universal, whether love or grief or longing or everything that makes up what we have come to call a life.

What I love about this poem is not just the devastation and longing it portrays, but also how it exists on multiple planes. On one plane, it is a poem of tragic proportions, but on the other, I could argue it is a poem about joy. Joy — there it is. You knew it was coming. There is joy in this poem. The craft inherent in the work of this poem allows for joy. Let’s find it.

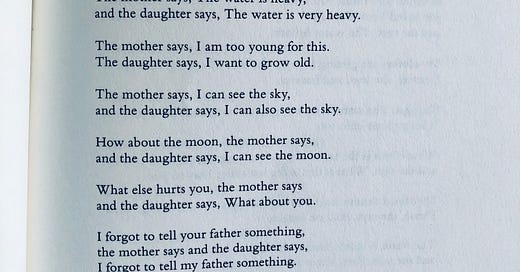

The craft of this poem is nothing short of marvelous. Like, truly. It is marvelous in its apparent simplicity. Notice the first two lines:

The mother says, I am afraid.

The daughter says, I am afraid.

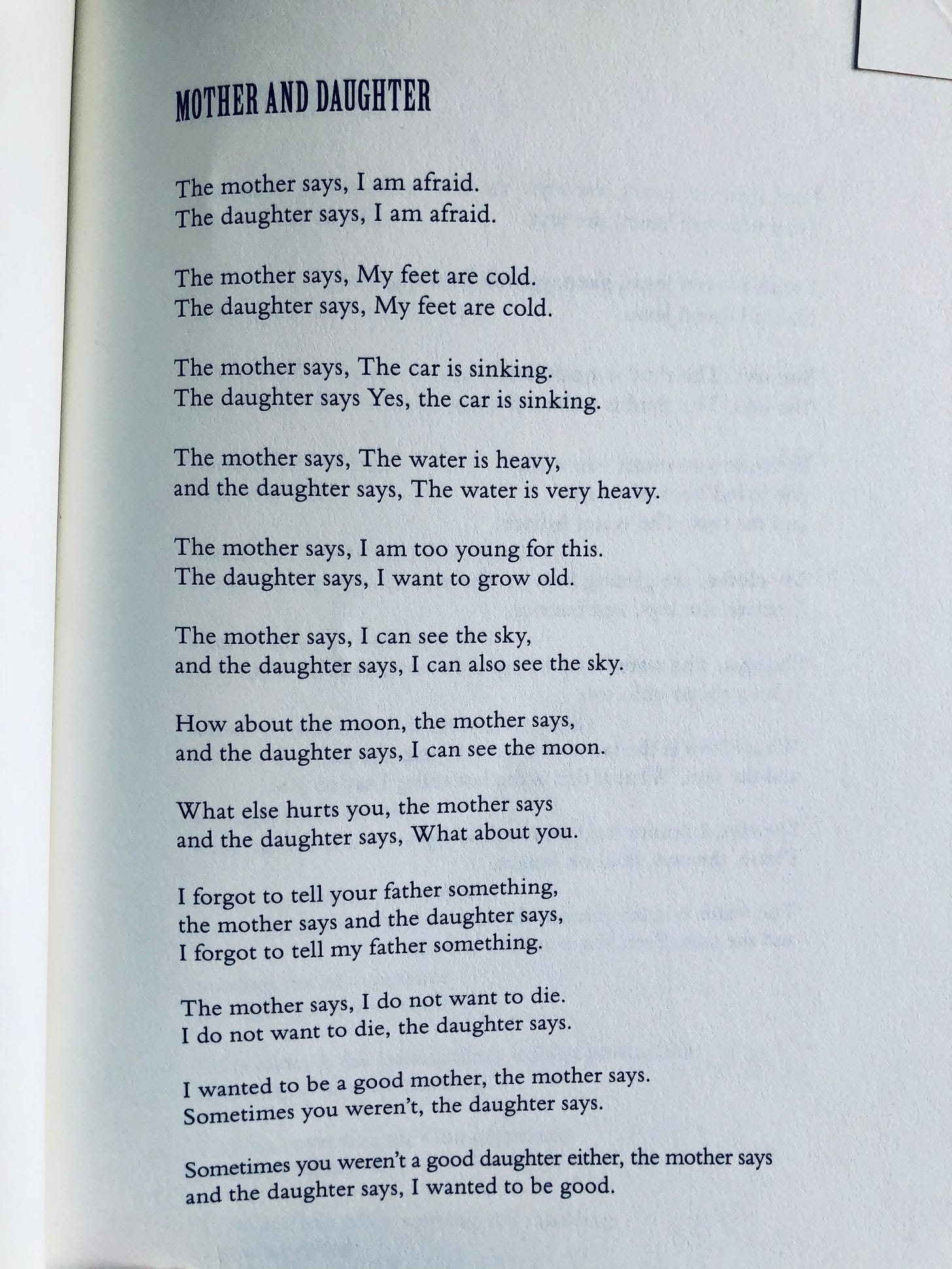

From the outset, the poem presents itself as a poem of fairly simple constructs. There are two characters. Mother. Daughter. They are both afraid. The poem utilizes direct language. Each moment of dialogue is rendered as a couplet. It is predictable. One character speaks, then another. As the poem progresses, the reader learns, through this dialogue, what is happening. In fact, what is happening — “the car is sinking” — is said twice. There’s no confusion there. The poem moves remarkably in this fashion — couplet after couplet, surface detail after surface detail — until it becomes universal.

But all of that exists on the surface of the poem. Notice the ebb and flow of the tension and unity between mother and daughter, how when the mother says “the water is heavy,” the daughter responds “the water is very heavy.” Those slight differences accumulate and then recede. They explore, without explicitly stating it, the differences between these two characters, whether a result of their lived experiences, their regrets, their desires, or their obsessions. Throughout the poem, the mother and daughter exist in tension with one another, even in the face of their impending death, but they, even as individual selves, also exist in tension with their own selves! It is the mother who is “too young,” and the daughter who wants to “grow old.” They contradict assumed narratives. And yet, despite these moments of disparity, mother and daughter are bound by unity, bound by how they each “forgot to tell [your/my] father something,” bound by “hurt,” bound by not wanting “to die.” They are in love together. In love with some things the same and some things different. In love with each other.

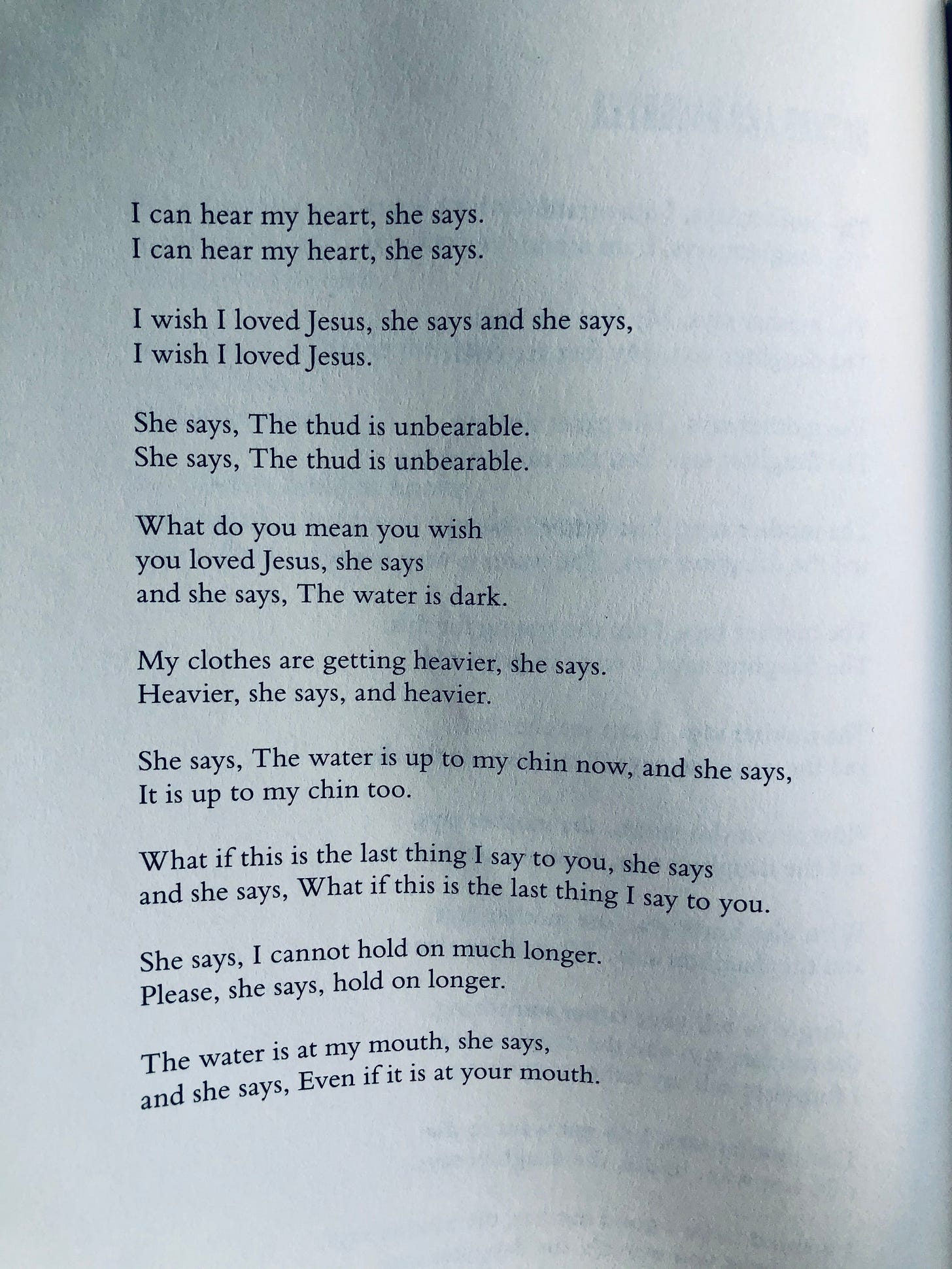

It is this ebb and flow of disparity and unity that gives the poem its humanness and, subsequently, allows it to become transcendent. But no moment does this more fully than the kind of invisible turn the poem offers as it moves toward its second page. Immediately after the white space that follows the line “I wanted to be good” — such a heartbreaker, truly, fuck, I mean, really — there is the blurring of specifics. Mother and daughter recede, and they collectively become the singular pronoun “she,” and, as such, the idea of who is saying what becomes harder to decipher, impossible even.

In that moment, too, the poem displaces itself. It becomes vague at times — “The water is dark” — and echoes against its own words — “Heavier, she says, and heavier.” But all of that — the uncertainty, the echoing — gives weight to the final two couplets. It’s hard to imagine four lines of poetry that can do what these four lines do:

She says, I cannot hold on much longer.

Please, she says, hold on longer.

The water is at my mouth, she says,

and she says, Even if it is at your mouth.

There is so much to unpack that it is best to let these lines stand as a testament to the human will to live and as a testament to the craft of poetry. The repetition of “she says,” the comma placement that slows down the breath, the subtle use of the word and before the final “she says” — these moments still the reader, still the moment, and capture love in that moment, and despair, and deep, utter humanness. It no longer matters who is who. And yet it does. How is the poem changed if the mother says those final words? The daughter? They are one and the same, and they are one and different. It stills me.

I said earlier that this poem has joy in it, and I believe it does. Maybe I just mean love. Maybe I just mean that there is love in these last lines. Love of one another. Love of life, even in the midst of tragedy. But there is also love in the speaker of this poem. The unnamed speaker. Maybe it is some kind of omniscient narrator, one who knows all. Sometimes when I read this poem, I imagine the speaker as the daughter’s father. And when I imagine that, I see a gentleness that exudes grace. I see the gentleness in the full line given to the statement: “I forgot to tell my father something.” I see gentleness in the line that reads “I wanted to be good.”

I like to imagine this gentleness because I like to see it as what a poem might aspire towards. In the gentleness of the speaker, I notice the fullness of these characters. I notice what, in another poem, might be seen as flaws. All this want. All this not-having-done. Mishap and mistake. To be clear, it is not the speaker who gives these characters their wholeness, but it is the speaker who has the grace to see the wholeness for what it is — the deep complexity of living in this world. It does not need to be redeemed, it just is. It can only be loved. There is no place for judgement in this poem. There simply cannot be. It is too late for that. And too early. It does not belong. In this portrayal, given over the course of these lines, there is such utter love, such compassion. I can’t get over it.

In the poem just before this poem, titled “In a Perfect World,” Charara writes:

What happiness to know more than the known world,

to believe in what cannot be seen.

It is that same happiness that permeates this poem of tragedy, as the speaker imagines a fullness of life that is not their own, a life — two lives — that the speaker cannot see, and never will. I want all poems to aspire toward this fullness when they can. I want my life to. It is not the same as believing in the goodness of people — an inherently flawed ideal. Rather, this poem speaks to the idea of believing in the people-ness of people, that, as people navigate a life populated by the tension of what if’s and certainties, there will always be a looking-back just as there is a hoping-for. There will always be regret, and doubt. There will always be a hand reaching for another hand. There will always be the ways in which we are taken away from one another and become singular in our moments of suffering, and there will always be ways in which we move with a kind of grace toward a shared experience. Life is lived in the in-between of these moments. Even at the end of a life, where this poem begins, it is still in between. I learn from it in that way.