From Against Which (Cavankerry Press, 2006)

I do try to write these posts about more than just — for lack of a better phrase — contemporary canonical poets. And I know Ross Gay is a poetic rockstar of sorts. But I was re-reading Against Which — from 2006, which feels like ages ago — and felt as moved by today’s poem as I did when I first read it.

What I love about Ross Gay’s work is, I think, what so many love about his work: its playfulness, its grace, its insistence on love. His work, along with Patrick Rosal’s, Thomas Lux’s, and late Raymond Carver’s, was an early example for me of how a man could write about the world while leading with something close to tenderness. In one poem, he writes:

I love to think

grace takes strange shapes

I love that. I love how it leans into unknowingness, how it assumes strangeness rather than its opposite. In another, he writes:

The bullet, like you, simply craves

the warmth of the body. Like you, only wants

to die in someone’s arms.

I love this, too. I love how it subverts violence into want and desire, how it pillows tenderness out of something once thought so hard, bracing, and stiff.

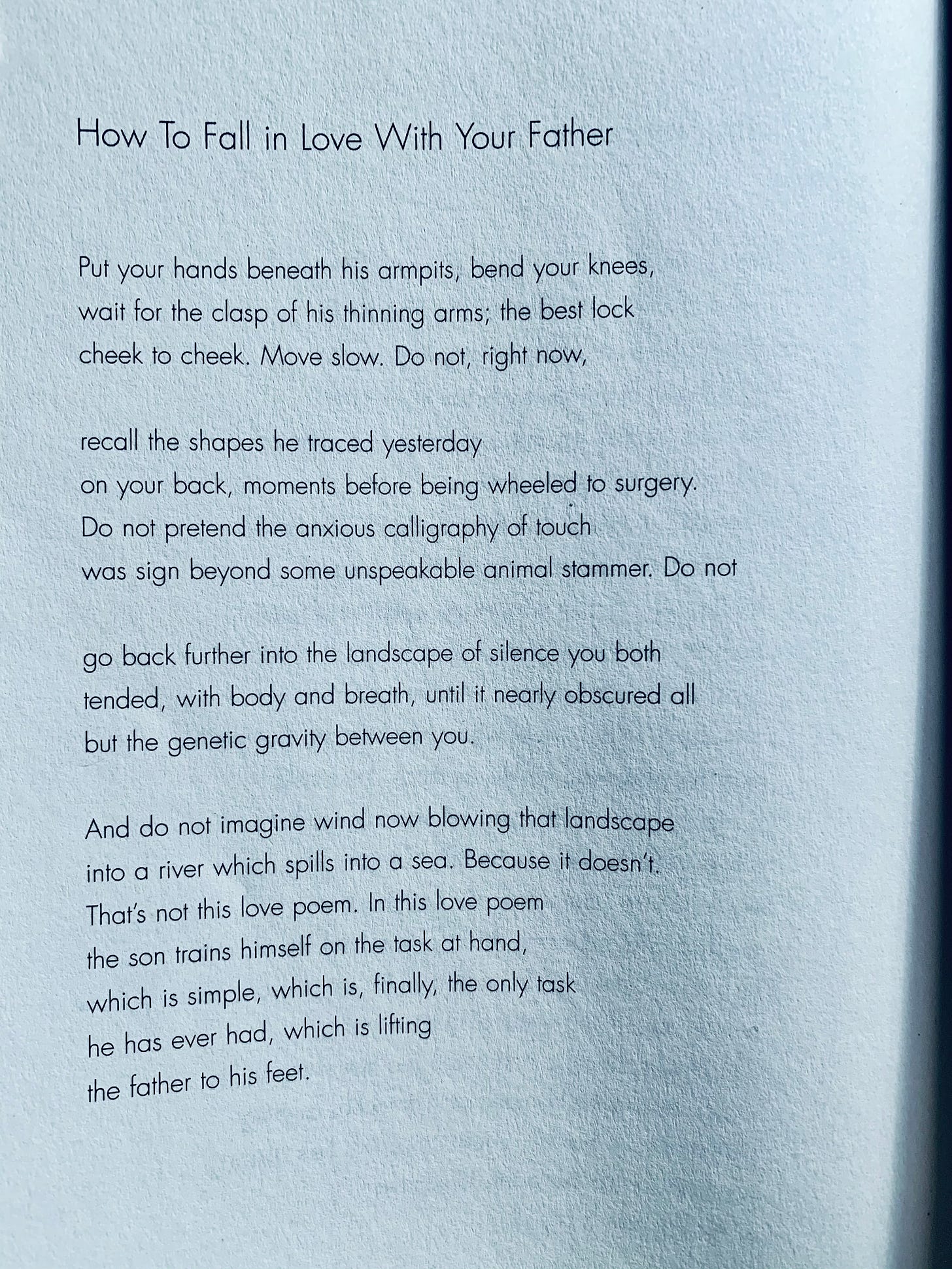

Today’s poem, in many ways, does a similar thing. It leads with love. It pushes against violence and silence. The title alone — “How to Fall in Love with Your Father” — does so much work. It tells us that love might not be, or have been the case. It introduces us to what might become love. It says here are some instructions.

Almost immediately, this poem becomes a poem of subversion. The “hands beneath his armpits” call to mind the hands of another poem about fathers: the “cracked hands that ached / from labor” in Robert Hayden’s poem “Those Winter Sundays.” The hands of Gay’s poems are hands of tenderness, hands of how-to-love. They are also the hands of a son. So often, a father’s hands are depicted (and idealized) as things turned away from bodies, and turned toward machines, labor, the earth. When they do turn upon bodies, it is often in violence. One of Adrian Matejka’s poems from The Big Smoke — an amazing collection centered on boxing — begins:

I’ve forgotten some prizefights,

the names of men I beat morethan they beat me

But Gay’s poem offers those hands back to the body in a way so full of love. They are not the hands of violence — whatever their history. And in their love, there is a sense of forgiveness of whatever violence might have occurred from the body of the father those hands now hold. The poem subverts the so often expected manual labor of sons and fathers — which is so often glorified — and turns the bodies back toward one another when they were once turned away. In doing so, the poem asks a question: what of power, when power so often fails us?

The poem makes me think of the ending of Stanley Plumly’s “Sonnet,” maybe my favorite poem about fathers. It details a father in his final moments, rising — or thinking he is rising — from bed. The last lines read:

I think of him large in his dark house,

hard in thought, taking his time.

But in fact he is sitting on the edge of his bed,

and it is morning, my mother’s arms around him.

Contrast that phrase “large in his dark house” with how Gay writes of the father’s “thinning arms” or his “anxious calligraphy of touch,” and you see the work Gay is doing to tenderize the father into someone so in need that he is finally capable of being loved. Maybe it’s because I recently listened to the rendition of Crosby, Stills, Nash, and Young’s “Helpless” from The Last Waltz, but I’ve been thinking about helplessness lately, and the way it exists as some final point, some final door, through which love might enter. That’s sad, isn’t it? That sometimes it takes helplessness to ask for help? That sometimes even in helplessness, we don’t ask for help? What to make of that, other than sorrow?

But back to today’s poem — that subversion of typical masculine expectation is seen every time Gay repeats the phrase “do not,” which signals every thing his speaker is attempting to unlearn or relearn from an existence characterized by the phrase “landscape of silence.” By continually repeating the words “do not,” Gay asks us, as readers, to think with him about what our expectations are around relationships, childhood, and masculinity.

But, at the same time, the poem — in its own sad way — succumbs to those same expectations, I think intentionally. You see the speaker caution himself:

Do not pretend the anxious calligraphy of touch

was sign beyond some unspeakable animal stammer.

Here, Gay’s speaker is essentially saying don’t be a poet. Don’t pretend there’s any meaning here other than the “task at hand.” As I read this, I feel a moment of deep sorrow, a moment where the speaker wants more than the moment at hand, wants a love language that does not exist, wants, more than anything, for a love to have happened and not for a love to maybe be happening. The speaker is insisting on presence because anything else will be avoidance, will be a moody dip into an ocean of past silence and violence. The speaker is insisting on work, even if an insistence on work — outside the work of love — is so often the cause of silence and violence.

But in the end it is the silence that stays with me. And it is the thought that, as life moves on, the things that can bridge silence seem to grow fewer and more far between. Years ago, I took care of my father — 73 at the time — after his own hip replacement. I knelt in front of him to put on his socks. I helped him out of bed. I put my arms around him. I held him.

When I read Ross Gay’s poem today, I think of how each sock I ushered up my father’s feet, each toenail clipped, was a way for me to say I love you, over and over again, when we had not said those words for so many years. And there is beauty in that story, but there is also great sorrow. There is sorrow especially in my father’s insistence to be independent, to say: no more, no more, no more. I see it in myself, too, this desire to abandon help, this refusal to ask for it. And why? What love poem, as Gay writes, is that?

These kinds of thoughts are what make me turn toward a genre of poetry that is not often discussed: women writing about fathers. It’s obvious that these kinds of poems exist, because these relationships exist, and yet, so often, what is celebrated — and I know I participate in this celebration — is the poem from son to father. I think of Sharon Olds, and her poem, “Late Poem to My Father,” which begins:

Suddenly I thought of you

as a child in that house, the unlit rooms

and the hot fireplace with the man in front of it,

silent.

When Stanley Plumly thinks of his father in that aforementioned poem, the father is “large in his house,” but here, in Olds’ poem, the father is a child. Later, the father is “a boy of seven, / helpless, smart.” The tenderness makes me want to cry. In the genre of son-to-father poems, a common theme is regret. Robert Hayden’s speaker in “Those Winter Sundays” repeats that canonical phrase: what did I know, what did I know? But here, with Olds, there is such a gesture of grace, of attempted understanding.

Ross Gay’s poem today is a poem of that same grace. It ends with love. And though that love is so imbued in the masculine — the “task,” the “lifting” — it is love nonetheless. It is love, especially, in the insistence that the silence of the stanzas before, the silence that could become an “ocean,” does not continue. I think of that silence so often. In an essay I wrote awhile ago, I said: “What is it about being a man? There are rivers we spend our whole lives damming.” I wonder about that question still.

Every love poem, I think, is a poem of grace. Because you can spend years in silence not knowing how to say I love you. Because you can spend years knowing what you need but not asking for it. Because you can spend years lifting, only to realize that you spent years lifting the wrong thing. Because someone’s hands can spend a lifetime in the blistered existence of the everyday only to spend a minute, years later, making calligraphy out of your skin. Because it only takes a second to be brought to your knees. Because it only takes a second for someone to lift you.

What to make of this? Perhaps to think of what Ross Gay means when he writes “That’s not this love poem. In this love poem…”

Maybe that’s a prompt for today. What’s not this love poem? What is?