Suzanne Buffam's "Enough"

Thoughts on asking.

Enough

I am wearing dark glasses inside the house

To match my dark mood.

I have left all the sugar out of the pie.

My rage is a kind of domestic rage.

I learned it from my mother

Who learned it from her mother before her

And so on.

Surely the Greeks had a word for this.

Now surely the Germans do.

The more words a person knows

To describe her private sufferings

The more distantly she can perceive them.

I repeat the names of all the cities I’ve known

And watch an ant drag its crooked shadow home.

What does it mean to love the life we’ve been given?

To act well the part that’s been cast for us?

Wind. Light. Fire. Time.

A train whistles through the far hills.

One day I plan to be riding it.

from The Irrationalist (Canarium Books, 2010)

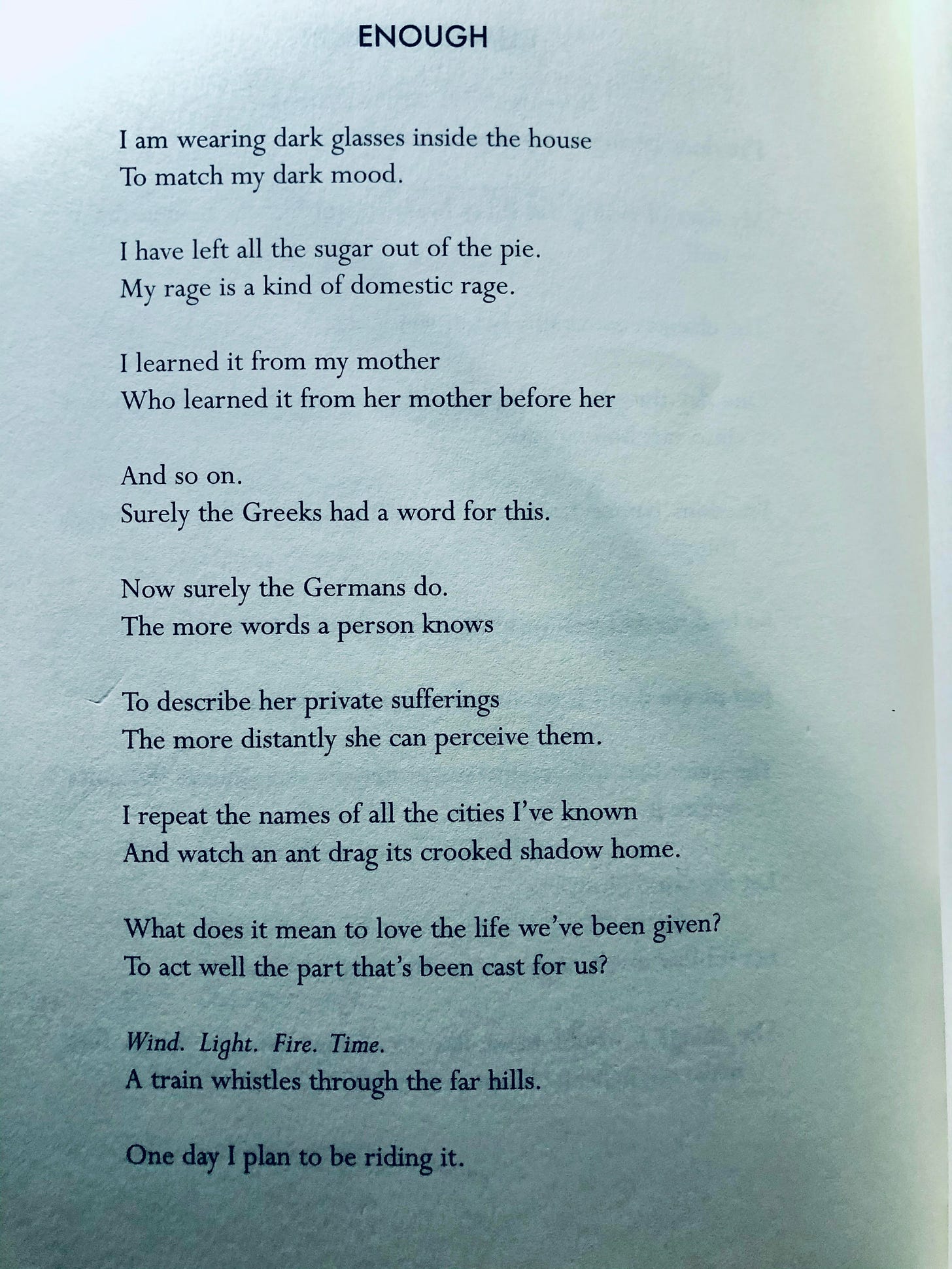

(And here’s how it looks on paper in case the formatting is wonky above)

I love Suzanne Buffam’s work. I find it wickedly funny and wickedly sad. She captures the despondence of being alive in a way that makes a poem seem like both the most necessary structure with which to capture such despondence, and also the most useless. I think it’s okay to say that poetry is useless sometimes. I think it’s a platitude to say it is useful all the time, or good, or whatever positive quality you want to ascribe it. This poem articulates that kind of despondence so well, and, yes, with a lot of humor. It begins, I think, with that humor, which is disarming. Those first three lines are so funny! I mean, c’mon:

I am wearing dark glasses inside the house

To match my dark mood.

I have left all the sugar out of the pie.

I imagine the speaker moving through the house, dark glasses on, intentionally participating in her sadness. It is a deft image, a lasting image, a funny one, and, the moment that fourth line appears, a deeply sorrowful one. The prior images transform into a singular image of “rage,” and, as the poem progress, the speaker’s rage becomes tethered to a litany of generational rage, experienced from woman to woman throughout the family. Quite swiftly, in just a few lines, the poem moves from humor to despondence, from ironic detachment to hopelessness. It is that kind of move that makes me love Buffam’s work, because it happens with such ease, almost, and then you’re sitting in despair wondering how you got there.

Just as this is a poem about generational, domestic suffering, it is also a poem about language:

The more words a person knows

To describe her private sufferings

The more distantly she can perceive them.

I see Buffam riffing here on the ever-present idea that if you can just a name a thing, then you can understand it. I think of all the times I’ve looked up the etymologies of words and used their literal pieces and histories to come to some deeper understanding of a feeling. And yet, despite that, there is still distance always — distance between what is named and what is felt, between moment and description. It’s a complex idea, and Buffam’s use of a medium comprised of language to critique the shortcomings of language gives some insight into her abilities as a poet.

Buffam is a poet, I’d argue, of multiple truths. Just as there is rage in this poem, there is also humor. Just as there is suffering, there is also a distance from that suffering. That distance is ironic, yes, and detached, yes, for much of the poem. I hear it in the speaker’s voice, the repetition of the word “surely,” and the short line that simply reads “And so on.” I imagine the speaker wearing her dark glasses as she writes the poem, maybe lighting a cigarette, almost chuckling as she intentionally distances herself from what is eating away at her, and what has eaten away at all who have come before her.

I am someone who usually has a hard time with irony. I find it off-putting, often privileged. I wonder, when I read an ironic statement, if irony is a privileged act, if a speaker’s ability to confront a situation with irony shows the distance they already have from that situation, and, as a result of that distance, the protection or security they are afforded as a result of that distance. But one could also argue the opposite, I imagine — that irony’s creation of distance is needed because of a lack of security or safety in the present moment, because one is too close to the subject, or too close to what could cause them harm. Maybe my own issues with irony are a result of my own privilege of never having had to use irony as a way to distance myself from harm. Maybe I should see irony the same way I see self deprecation — which I engage in frequently in order to buffer myself from shame. I forget that language can be both the bridge that crosses a river and the river beneath that bridge.

Regardless of this critique, I love the way Buffam’s poem turns after those opening lines. It turns with great vulnerability, great openness. It performs one of my favorite poetic moves. An all time great move. A beautiful move. A dunk from the free throw line. A flea flicker. A [insert non sports metaphor here]. It does the best thing ever: it asks without expectation of an answer. It simply fucking asks some questions:

What does it mean to love the life we’ve been given?

To act well the part that’s been cast for us?

I adore this poem because of this move in particular, because of how it exists immediately after the balance that Buffam strikes throughout the poem — aware, I think, of the cool detachment of her speaker, of the learned hopelessness. When the speaker offers these questions, they enact a volta of sorts, a turn from the very specific ordinariness of the speaker’s rage to the wildly universal question: What does it mean to love the life we’ve been given? Here, the poem now becomes not just a poem about private suffering, but also a poem about the universality of despair, the fear of not-being-enough. The question has echoes of Seamus Heaney’s question from “Badgers”: “How perilous is it to choose / not to love the life we're shown?”

It makes me think of Denis Johnson’s lines at the end of his poem “The Monk’s Insomnia”:

It was love that sent me on the journey,

love that called me home. But it’s the terror

of being just one person — one chance, one set of days —

that keeps me absolutely still tonight…

Buffam and Johnson’s poems talk across the pages with one another. You notice it in Johnson’s terror leaving him completely quiet. And you notice it in the way Buffam answers her own questions with a series of words deeply wound up in the earth itself — “Wind. Light. Fire. Time.” — before hearing a train whistling in the distance. In other words, both poets come to an understanding that there are no answers. Both Johnson and Buffam know this, I think, and accept it. I think we all do, at one point, when our search for answers leaves us answer-less time and time again. Instead, in the wake of having no answers, we are left often with stillness as what fills the space of uncertainty. I used to think of stillness as a waste. I used to think of breath as something purely mechanical. I used to think any question that couldn’t be answered would become a question eventually answered. I don’t think those things anymore. Poetry — more particularly, poetry steeped in the act of witness and the dwelling-in of mystery — helped me understand that.

In the same book, The Irrationalist, that this poem is from, Buffam has another poem, titled “On Duration.” It exists as one of many very short poems in a section titled “Little Commentaries.” It goes like this:

To cross an ocean

You must love the ocean

Before you love the far shore.

I fucking love this poem. I love the way it feels like an axiom. I love its littleness, its risky approach to being almost-platitude-like. I love the way it riffs on the form of a platitude while also stating what I’ll call the “should’ve thought of it before kind of obvious.” I love the certainty with which it expresses something so close to impossible — loving the ocean that we are in. I love its joy and its hope. And I love that both this poem and the poem above — “Enough” — exist in the same book. I love what that says about the capability of poetry to express, dwell, offer, hope for, detract from, critique, et fucking cetera.

And more importantly, and lastly, I love that this little poem doesn’t tell you how to “love the ocean.” So when I hear Buffam’s speaker asking: What does it mean to love the life we’ve been given?, I also hear her reaching back to the poems that come before, and asking: What does it mean to love the ocean? And that’s okay. Some questions will always be asked. (Think, Jane Hirshfield: "There are questions that never run out of questions, / answers that don’t exhaust answer.") And when a poem asks questions rather than pontificates answers, when it approaches the page as a space of seeking, not of knowing, then it models a kind of relationship with the world prioritized by some degree of intellectual humility, which I’d argue offers a wider entryway — than intellectual hubris — into companionship, solidarity, grace, or whatever kind of betterness is out there.

I think of some of my favorite poet-questions out there:

Raymond Carver: “And did you get what you wanted from this life, even so?”

Seamus Heaney: “Is there a life before death?”

Rita Dove: “Who claims we’re mere muscles and fluids?”

Sophie Klahr: “Will we heal? There’s a light / that pours from us — is it light?”

Wanda Coleman: “what god must i declare dead?”

Alison C. Rollins: “Why do you dread being forgotten?”

Carolyn Forché : “To what and to whom does one say yes?”

Maybe I shouldn’t find existential comfort in the existential discomfort of these questions. Oh well. I still do. It makes me know we are alive.