Tracy K. Smith's "Poem in Which Nobody Says 'I Told You So'"

Thoughts on the collective imagination.

Poem in Which Nobody Says “I Told You So”

The point is, you won’t necessarily know

Whether you’re living a science fiction reality.

Just as you won’t learn until after the final episode

Whether the captain meant all he said about aviation

And his wife. And what were you doing, anyway,

In that chamber? Signs everywhere whispered Caution.

In the past, horses were the chief vehicle

Of man’s dream of escape. Then the locomotive.

Now we can lose ourselves in six dimensions.

I plead the Fifth. Lust is real. Love

Is a momentary lapse of treason. Technology

Means there is no such thing as persistence

Of vision. The West was never won.

You were never the one in the many.

But oh, the many…

from Duende (Graywolf Press, 2007)

This is maybe my favorite Tracy K. Smith poem, which is saying a lot, because there are Tracy K. Smith poems where she writes things like:

Freedom is labor

To labor at oneself

Or even things like:

Everyone I knew was living

The same desolate luxury,

Each ashamed of the same things:

Innocence and privacy.

All that to say, when I read Tracy K. Smith, I know I am reading someone whose finger seems on the pulse of something so real about America. And I think about that now, reading today’s poem fifteen years after it was published, and how it begins:

The point is, you won’t necessarily know

Whether you’re living a science fiction reality.

It’s hard to say — or maybe it’s not — but it seems to me that no two lines of poetry seem more well-suited toward describing our contemporary moment than these. There’s a part of me that loves the resistance they seem to accept, the way that someone reading this poem might be turned off by the interjection of science fiction into poetry, the way that such an interjection is made seriously — the point is — and without a hint of anything other than truth.

I think I’m thinking about this poem because I just read Amitav Ghosh’s The Great Derangement, a book about the relationship between contemporary ideas of narrative and the reluctance to deal — on a global scale — with climate change. In it, he writes:

The climate crisis is also a crisis of culture, and thus of the imagination.

Ghosh points to the way in which contemporary ideas of the novel have limited our ability to imagine different worlds, particularly how the distinction of what is deemed “literary” has affected our collective ability to lean into imagination as a tool for survival. Ghosh writes:

The great, irreplaceable potentiality of fiction is that it makes possible the imagining of possibilities.

And yet, Ghosh argues, the constant dismissal of science fiction and magical realism from the realm of serious literary fiction — as well as the ways that realist trends in narrative have focused on moral individualism rather than the messy complexity of the imagination, the spiritual, the collective, the body politic — has made this “imagining of possibilities” less likely and less possible. He writes:

In other words, what is banished from the territory of the novel is precisely the collective.

I see some of these points echoed in Smith’s opening lines, which speak about the imagination without using the word. These opening lines seem to argue that our collective lack of imagination — a thing dulled by consumerism, capitalism, and the like — has obscured our ability to see beyond the present, to see around the corner of where we are. Or, rather, to see clearly where we are right now. If this is the case, Smith seems to be saying, then we are locked in an obscured view of the pure present of our existence, a present that might not seem like a “science fiction reality,” but might very well be.

I think of the lines that come later in the poem:

And what were you doing, anyway,

In that chamber? Signs everywhere whispered Caution.

It’s funny, because in Ghosh’s book, he writes:

I suspect that human beings were generally catastrophists at heart…

There’s something about our avoidance of disaster that leads to more disaster. And yet now, with the caution signs alluded to by Smith, disaster is at the heart of our ever-present narrative. To be alive is to bear witness, constantly, to a constant cautionary tale. Perhaps this is why Smith’s question above rings so clear: what were you doing, anyway? It’s the kind of question someone might ask years and decades and centuries from now — if there are centuries to come — and yet it is also a question that Smith is asking in this poem. What were you doing, anyway?

One power of poetry is the way in which it can articulate immense narratives and critiques in an unbelievably condensed form. Smith does that in the middle of today’s poem:

In the past, horses were the chief vehicle

Of man’s dream of escape. Then the locomotive.

Now we can lose ourselves in six dimensions.

These three lines articulate, with real clarity, an image of the scope of technological advancement as well as a critique of the necessity of such a thing. It reminds me of a Super Bowl ad this year, one that advertised the metaverse. In it, a neglected stuffed dog puppet thing who is both animate and inanimate and once played music at some now-closed bar gets a sort of second chance through the metaverse to be — I don’t know — its best self? The ad begins with the dog joyfully singing to a crowded bar. Then the bar closes. Then the dog is made to work odd job after odd job. Then the dog is thrown out, left along a highway, wedged into a garbage truck. Finally, in his final odd job, someone puts these metaverse goggles on him, and he gets to play in a virtual band in a virtual bar with his virtual friends.

I know the commercial was intended to be a feel-good story about the way that technological progress — namely, the metaverse — can rescue our lives and restore us to our old, better selves. However, to me, the commercial’s main takeaway was that our lives have been parceled out and ruined to such extreme lengths that the only way to make ourselves feel fulfilled, validated, and joyful is through similarly extreme lengths: other universes. The commercial did not communicate the beauty of the metaverse; instead, it relayed the absolute failings of society, which treated that stuffed dog — who, let’s be honest, is just a cute stand in for each of us — as an object, depriving him of both joy and the means to access real, worldly joy. As our needs for escape have grown because of the structures of our society that continue to alienate us, so too have the technologies that attempt to cater toward such escape.

I’m thinking of these three lines from today’s poem:

Technology

Means there is no such thing as persistence

Of vision.

It’s a mouth-and-brain-full of an idea, packed into a sentence that tumbles over three lines. But it’s also a testament — per usual — to the way that critique can be couched so concisely within a poem. It’s a bold, powerful statement, one that goes against the narrative of the American mythology — the idea that technological progress is the sign of a vision being acted out, a persistent vision, with aligned values and ideals. Smith seems to be arguing that technology, as we have come to understand the word, is actually the opposite of persistence. Perhaps it is, in some ways, a kind of scattering of vision, a breakage, a fragmentation. Perhaps it is even a stunting of vision, a stalling.

I’ve been chewing on this idea for a bit, ever since reading Ghosh’s book and thinking about the opening lines of today’s poem, which are lines that pop into my head in the middle of a day. Lately, they pop into my head a lot.

What I’ve been thinking about is the fact that one of the enduring beliefs about technology in our culture is that it is, by its very nature, imaginative. I think that’s an idea that is seemingly hard-wired into our brains, to the point where every new Silicon Valley product or idea or work-streamlining-app is hailed as some imaginative solution to a previously unsolved problem. But, I often wonder, what is the problem? Did some tech company just make it up? Recently, I was listening to an episode of You’re Wrong About where Sarah Marshall and Anne Helen Peterson were talking about email. I’m generalizing here, but Peterson mentions how email technology opened the floodgate for new, rapidly developing technological innovations that were created to solve the problems caused by the technological innovations that came before. In other words, the tech world became — and still is — this kind of mutant ouroboros, billing each new innovation as a life-hack, an easier way, a faster thing — when really each new innovation is simply a solution to the innovation that came before. In still-other words, maybe we would be better off without so much of what is told makes us better off.

In a similar vein, toward the end of Willa Cather’s Death Comes for the Archbishop, one of her characters says:

Men travel faster now, but I do not know if they go to better things.

It’s funny, almost absurd, reading such a sentence and feeling it leap out of a book published in 1927. As Smith writes, “Signs everywhere whispered Caution.” For a long time, people have warned about the faster, the sleeker, the better, the newer. For a long time, those people have been ignored, or patronized, or dismissed, or some version of one or all three of those things. It’s happened so often — the warning, the dismissal — that it feels almost like a cliche to even mention it.

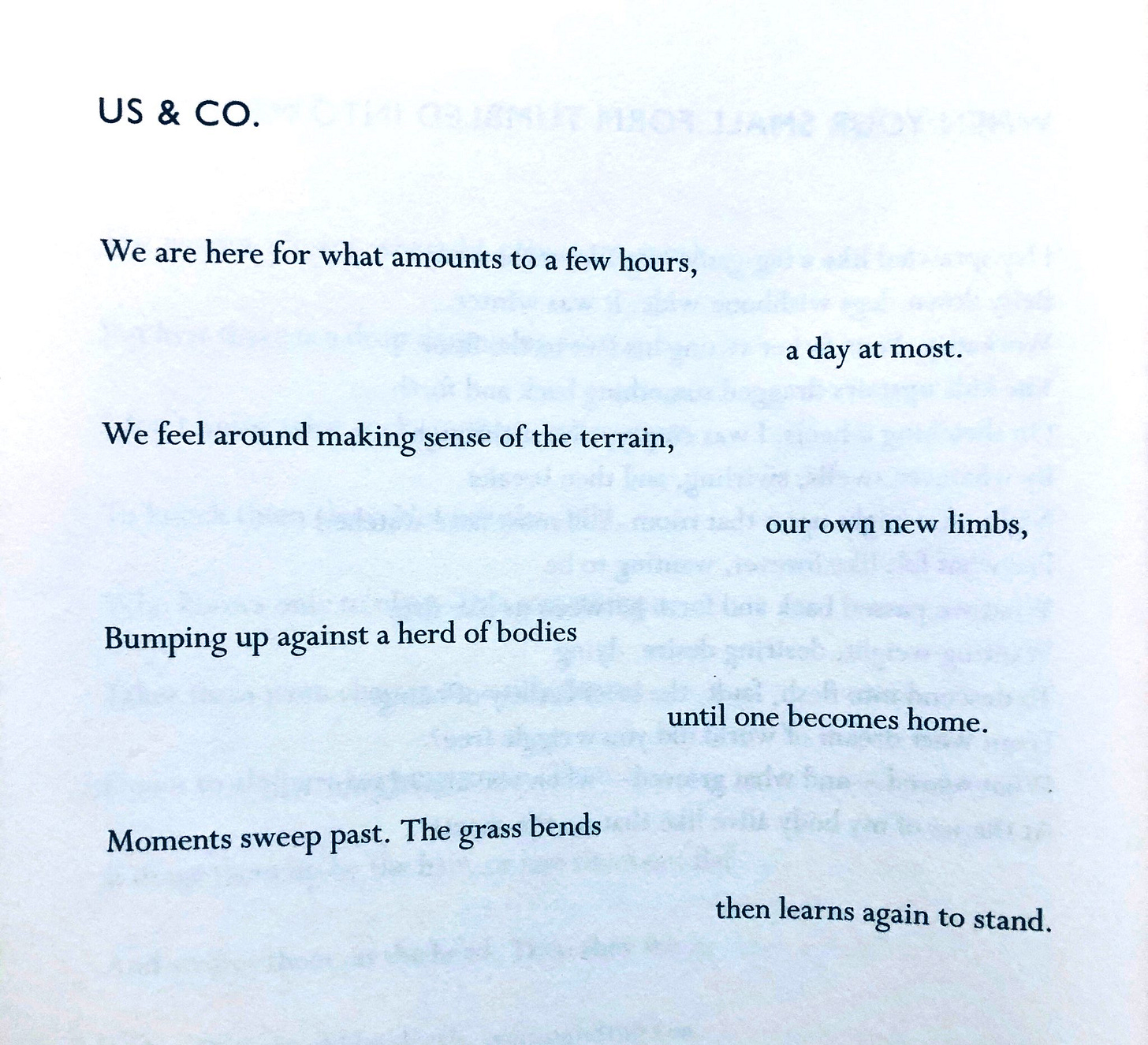

I find myself thinking about another poem, “Us & Co,” by Tracy K. Smith, from her book Life on Mars, the title of which feels in absolute conversation with today’s poem. Here it is in full.

Such a poem makes me think again about Ghosh’s critique of fiction — the banishment of the collective. Here, in Smith’s poem above, the “we” is all-encompassing. It is, in some ways, the origin of the poem, which, in such a short space, attempts to get at the all-ness of our collective experience, which is both a shared experience and a fundamentally short experience. A poem can do this. It can speak in collective terms about big ideas. It can eschew individual plot for something larger: collective identity, and how it connects us to the earth, and how we handle such a thing, and how we fail at handling such a thing.

It’s interesting, too, that today’s poem utilizes the second person. That it feels almost accusatory in nature. And that, even though it seems to be speaking to an individual you, it is also speaking to a you that is perhaps great and damaging: the American mythology, a you that has, throughout its history, often denied a we, despite utilizing a we (ie. we the people). Because, look, notice how the poem ends:

But oh, the many…

There is that we that has been denied. That collective. That longing for solidarity, something truly shared.

The reality that we collectively live in is a reality that is deeply, intentionally alienating. And maybe that is why it can be hard to see and name and critique. Because loneliness is at the heart of it. And shame, I think, can be at the heart of loneliness. Sometimes it feels like critiquing this reality is the same as critiquing oneself.

What I want most days is the kindness that comes from humility. The soft laugh that escapes my mouth when I say to myself I can’t believe I thought that. The hours I spent with my friend George in Denver, talking in the same room as the world lingered with us, talking about who we were and how we have grown and what we missed and how we have been wrong, talking about what scared us and what made us laugh and how we are — and will always be — so different and yet still so much together in this life we have that is both shorter and longer than imagined. What I want most days is that last word: imagine. What I want is the way that imagination — when it is real and true — looks like a persistence of vision and value. The way it is a desire to see the world as it is and as it could be, which sometimes means thinking about it as it once was, before so much — pretending to be so little — fucked it up. I think imagination can look like humility. I think we are rarely taught that.

The other day, on a college trip with my high school students, we found ourselves on a school’s organic farm. A group of us walked up this slight rise, where a single, solitary woman was tending a big garden. She saw us, and I — scared for some reason to disrupt her — introduced her to our group. She smiled immediately, and dropped everything to show us around. At the end of her little tour, she kneeled down and plucked a couple flowers from the ground. She said we could eat them, and my students could not believe it. Me neither. But we took them from her, and we ate the little colorful petals, which tasted like licorice. It was the most beautiful thing to be a part of. And what I am trying to say is that it happened. It happened while you were doing something beautiful or while you were feeling alone or while you were feeling happy or scared or anxious or burnt out. It happened, and it was so simple and good. And it happened in the same world I live in, which is the same world as you, which is the same world as all of us. And I could not have imagined it, but now I can, and I think about it all of the time. I am thinking about it now, and longing for such gentleness to repeat itself, again and again and again.

"What I want most days is the kindness that comes from humility"

this line got me. more and more of the softness, the sweetness, the kindness...

Nasturtiums are very tasty, pungent. Violets too, but sweeter. I love the concept of imagination being associated with humility. Thank you for such thoughtful and piercing reflections.