Lucille Clifton's "Atlas"

Thoughts on a poetry of intimacy despite distance.

Atlas

i am used to the heft of it sitting against my rib, used to the ridges of forest, used to the way my thumb slips into the sea as i pull it tight. something is sweet in the thick odor of flesh burning and sweating and bearing young. i have learned to carry it the way a poor man learns to carry everything. from The Book of Light (Copper Canyon, 1993)

This is a poem that rewards and rewards and rewards the light of constant attention. When I first read Clifton’s The Book of Light, I glazed over this poem, not spending enough time with it to really feel it. It’s a beautiful book, The Book of Light, and it contains in it these widely-shared lines of Clifton’s:

won't you celebrate with me what i have shaped into a kind of life? i had no model.

It’s hard, I believe, to find a few more generous lines of poetry than these, which lead into a depiction of the pained loneliness of the marginalized self (“born in babylon / both nonwhite and woman / what did i see to be except myself?”) before ending with lines that are written with such remarkable clarity and depict such strength in the face of what should not have to be faced:

come celebrate with me that everyday something has tried to kill me and has failed.

So yes, when I first read Clifton’s The Book of Light, I was struck by the light at the heart of her poems, though I didn’t find myself returning to today’s poem. And then I did. And I read it again. And I read it one more time. And another. It begins with a single, flowing sentence:

i am used to the heft of it sitting against my rib, used to the ridges of forest, used to the way my thumb slips into the sea as i pull it tight.

Here, we are introduced to the idea of Atlas as a speaker. Atlas — the figure from Greek mythology who, punished by Zeus, is forced to hold up the entirety of the heavens. Here’s a passage from Hesiod’s The Homeric Hymns:

And Atlas through hard constraint upholds the wide heaven with unwearying head and arms, standing at the borders of the earth before the clear-voiced Hesperides.1

I think that’s what took me so long to enter into this poem. I didn’t see it; therefore, I didn’t feel it. I didn’t see that hunched figure of Atlas holding up the weight of the world, so popularized through statue after statue (though this is a misconception; Atlas holds up the celestial spheres, not the planet earth upon which we live, but for now, we will allow such a misconception, as the poem — and so much of art — is based on it). Yes, I didn’t see the poem. I allowed myself to read the poem without seeing it, and, as such, I glazed over it.

To spend time with this poem is to see and feel the depth of Clifton’s work as a writer. It exists, in this poem, in two parts (at least for me) — the imagistic and the critical.

As an image, this poem is so richly rewarding. Notice those lines quoted above. When I read them aloud to myself, I can almost taste them; they are so visceral. The heft of it. The ridges of forest pressed against my rib. The thumb that slips into the sea.

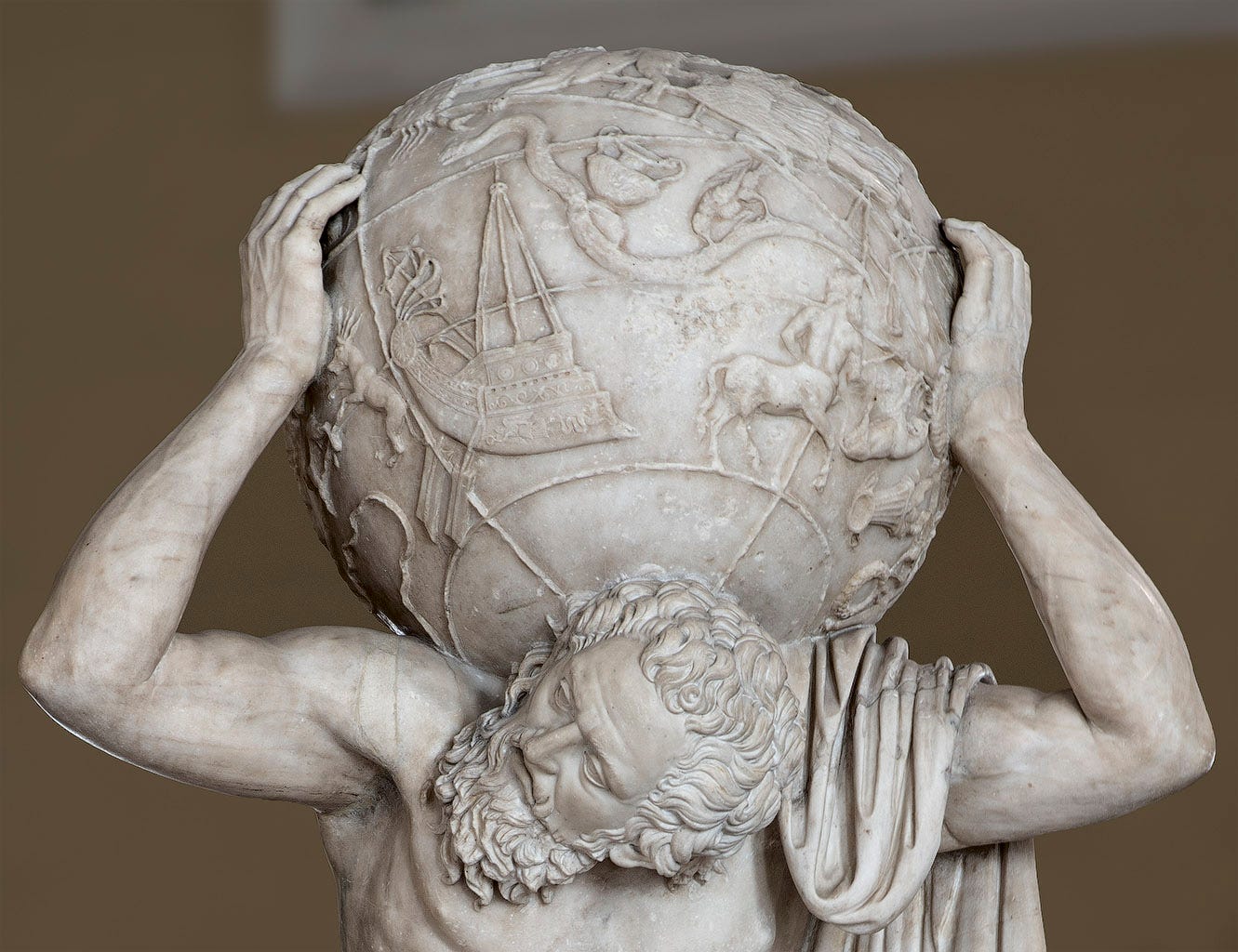

Here is a close-up of the Farnese Atlas — holding up the sky, a world of many worlds.

In full view, this Atlas is hunched over, seeming to be in the midst of groaning, thighs flexed, one knee balanced on a support, every inch of the body in a posture of deep, relentless effort. There is almost a sense of quivering. And it is that effort — and subsequent pain — that I feel Clifton capturing in her lines. The phrase used to is repeated three times, but what Atlas has grown used to is something utterly inhuman: the unending weight of the entire world, the pain of forested woods pushing and pricking into his bare back, the way, adjusting for some kind of grip, a thumb slips into the wetness of an entire ocean. Do you feel it now? The image? The pain? Do you feel the pangs of effort? I do. Now, when I read this poem, I feel a prickling sensation in the middle of my back. I feel pinecones against my skin. I feel my body tense. I sense my stress.

That sense, that feeling — that is Clifton’s doing. It is the jarring, poet-driven work of image-making. In just a few lines, Clifton captures that ready-made image — the person holding the world on their shoulders — and adds the intimacy of peculiar and particular and real details. It’s not just an ocean that the thumb moves through. It’s the saltiness of it, the muddy bottom, the wave created as the thumb attempts to find hold. And it’s not just the forest ridges against the back. It’s the reprieve of them, the world turned this way and that as the person struggling to hold the world tries to find a more comfortable way of holding it all, even though there is no way that could be called comfortable at all.

Part of the beauty of poems — or any kind of art — is the way that they allow us (if we choose to, yes, if we choose) to reconsider what we have already come to say we know. It only takes an image, sometimes. It only takes a word, a subversion of a cliche, something turned once or twice in the same light to see if it reveals something entirely different. The light is always there. Word-making is the act of turning our bodies in this light — our minds, too, our imaginations — to see what else they show and what else they hold.

But one beauty of Clifton’s work is the way in which she is not just concerned with the image; she is also so concerned with the way an image can become critical, can become a vehicle for the act of criticism itself. Consider her poem “jasper texas 1998” — written in dedication to James Byrd Jr, who was brutally murdered by three white men in Texas in 1998. The poem reads, in full:

i am a man's head hunched in the road. i was chosen to speak by the members of my body. the arm as it pulled away pointed toward me, the hand opened once and was gone. why and why and why should i call a white man brother? who is the human in this place, the thing that is dragged or the dragger? what does my daughter say? the sun is a blister overhead. if i were alive i could not bear it. the townsfolk sing we shall overcome while hope bleeds slowly from my mouth into the dirt that covers us all. i am done with this dust. i am done.

In the poem above, Clifton’s words are at once image and criticism — metaphor and reality at the same time. They come from distance and then immediately shatter the illusion of distance. Indeed, they come out of Clifton’s life and then inhabit the loss of Byrd’s life. Her words embody death itself — if i were alive i could not bear it. In this way, Clifton’s work illuminates the way in which intimacy can be reached despite distance. They make clear how radical the act of compassion truly is, the distance it makes possible to overcome.

I did not think of today’s poem as something deeply critical until I thought of what it made me think of. And then I remembered what I always think of when I think of Atlas, by virtue of living in New York City: the art-deco stylized statue of Atlas adorning Rockefeller Center.

That Atlas — pictured above — differs from the Farnese Atlas. It differs, too, from the Atlas of Clifton’s poem, who, we learn at the end of the poem, is a poor man who has learned to carry everything. The Atlas that stands outside of Rockefeller Center is 15 feet tall, wearing a face of aggrieved almost-annoyance rather than weariness. He is not slouching, but is rather cradling the entirety of the celestial heavens in the wide spread of his arms. His body, wrought in the art-deco style, is lined with deep definition, a definition that signals confidence over struggle. I find him terrifying. It is as if the Atlas standing in Rockefeller Center is emblazoned with this passage from Ayn Rand’s objectivist-and-capitalist-lauding novel Atlas Shrugged (many editions of which have used this aforementioned Atlas as its cover):

It's not that I don't suffer, it's that I know the unimportance of suffering. I know that pain is to be fought and thrown aside, not to be accepted as part of one's soul and as a permanent scar across one's view of existence.

Yes — the terror at the heart of the Atlas in Rockefeller Center is the way in which the statue stands as something worth striving for. There is no compassion at its heart; there is only dominance.

There is something about Clifton’s poem that simultaneously subverts this dominant worldview while positing and modeling something more radically compassionate in its place. In those final three lines, Clifton introduces class into the poem, which also introduces a sense of value, which also introduces a sense of surprise. Clifton takes the dominant image of Atlas — strong, capitalistic, enduring, individualistic — and rescues it from within the limited frame that it exists. She gives the image humanity. She gives it poverty. And, in doing so, she reminds us not just to constantly question the images and mindsets of dominant culture, but also to witness, remember, and protest against a reality that often forces its most disenfranchised members to carry the most. In this way, we begin to see Atlas with a deep compassion and love. We see the way it could be him — the poor man who has learned to carry everything — speaking as the voice of Clifton’s poem, in the same way as it could be Clifton herself, the one who asks:

won't you celebrate with me what i have shaped into a kind of life? i had no model.

Because yes, the Atlas looming in Rockefeller Center is not actually a model. There is an inaccessibility to him. A distance. A real value-less-ness. All of this reminds me of a passage from John Berger’s Ways of Seeing. In it, he writes:

The average work…was a work produced more or less cynically: that is to say the values it was nominally expressing were less meaningful to the painter than the finishing of the commission or the selling of his product.

The values at the heart of Atlas’s mythological story (punishment, marginalization, endurance, ordinary limitation) feel less important to the statue sitting outside of Rockefeller Center than the values of the extrinsically motivated idea of its commission. That is to say, the statue has come to symbolize the aims of who it was commissioned by, has come to symbolize the idea of wealth, capitalistic individualism (as represented by the art deco style, the clean lines and angles), upward mobility, endless striving, pursuit at all costs. It is less art than publicity, and, as Berger writes:

According to publicity, to be sophisticated is to live beyond conflict.

Maybe this is why the Atlas outside of Rockefeller Center — who has become synonymous with the modern world — seems almost unburdened, and why the celestial body which he is holding seems airy and unreal. There is no conflict at the heart of him. There is no reality.

Poetry, thankfully, does not have to be publicity. Clifton reminds us of that. She returns Atlas to his humanness. Where publicity and advertisement remind us of our distance — oh, I could never be like that, though I wish I was or look at all that I do not have yet — Clifton once again uses language and thought and value to reduce the distance between all of us. Instead of feeling the rampant alienation that I do when I see the modern statue of Atlas sitting in the shadow of the skyscraper, I read Clifton’s words and feel a sense of communion. I see the ways in which many people are carrying a whole world. I see the metaphor made real.

The first line of Clifton’s poem “my dream about the second coming” reads:

mary is an old woman without shoes.

I think of this as a radically compassionate line. I think of it as being clear enough to see or imagine how things really are, how things might really be, how things might have been or could have been.

The final lines of today’s poem do the same work. They render the world real again; they free us from the mythology of distance, the long-told lies of dominance. They remind us to look again at what is here in this world, and who is here. They ask us to question what we choose to strive towards, and why, and how. And they ask us to wonder about whether or not we witness who is being forced to strive and suffer too much, or unfairly, or inequitably. In doing so, they remind us of ordinariness. They remind us of the work of choosing to see. They do all of that work in a few short lines, and I think they do that work because they come from a place of value and care, which is a place that art can come from, but only when it makes the choice to see. It must make that choice. And these days, so often, to make that choice, one must choose against so much.

A Note:

If you’ve read any of the recent newsletters, you’ve perhaps noticed that I am offering a subscription option. This is functioning as a kind of “tip jar.” If you would like to offer your monetary support as a form of generosity, please consider becoming a paid subscriber below. There is no difference in what you receive as a free or paid subscriber; to choose the latter is simply an option to exercise your generosity if you feel willing. I am grateful for you either way. Thanks for your readership.

Hesiod. The Homeric Hymns and Homerica with an English Translation by Hugh G. Evelyn-White. Theogony. Cambridge, MA.,Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1914.

I am an old woman, never pregnant, with no children, by choice, grateful to have found your meditations, this one especially, with Lucille Clifton's poems.

When he was a boy, my father was given a tiny Atlas figurine made of metal. When I was a small girl, his oldest of three daughters, he gave it to me. The globe could be opened. I treasured the gift and kept cough drops in it. When my only nephew, my father's only grandchild, was a small boy I gave it to him, showing him that when it was turned upside down, it looked like Atlas was standing on his head on the top of the world. My father took a photo of my mother in front of the Atlas statue at the Rockefeller Center when I was 32 years old. My nephew is 30 years old now, unmarried, with a son of his own. He carries all that he can bear. He is not alone.

Reading this as a woman who has experience “bearing young,” I pictured that space she is holding as her flesh, the stomach that no longer looks young and flat but old and rolling. The models, literally, do not show us a picture of womanhood in older age. Yet many of us wear these bellies as testament to living.